Two Poems by Tomás Baiza

We of Mexican Mothers

We of Mexican mothers are nothing alike, except

in that we break the surface,

gasping,

from the ear-popping depths of that

most intense form of

maternidad.

We of Mexican mothers know the difference between

Swiss Miss cocoa and

Abuelita and

Ibarra Auténtico.

We know because we’ve breathed in until

our heads swim from the earthy musk of

our Mexican mothers’

pride,

exertion,

joy,

and their bitterness from

maintaining and gatekeeping

a culture.

We of Mexican mothers know that

some mornings are for arroz con leche, but

others are for Fruit Loops or Lucky Charms

because the alarm clock battery died

in the middle of the night

and now

everyone’s waking up late,

and now

everyone’s running around the house,

panicking over how we’re all bien jodidos

and there will be hell to pay,

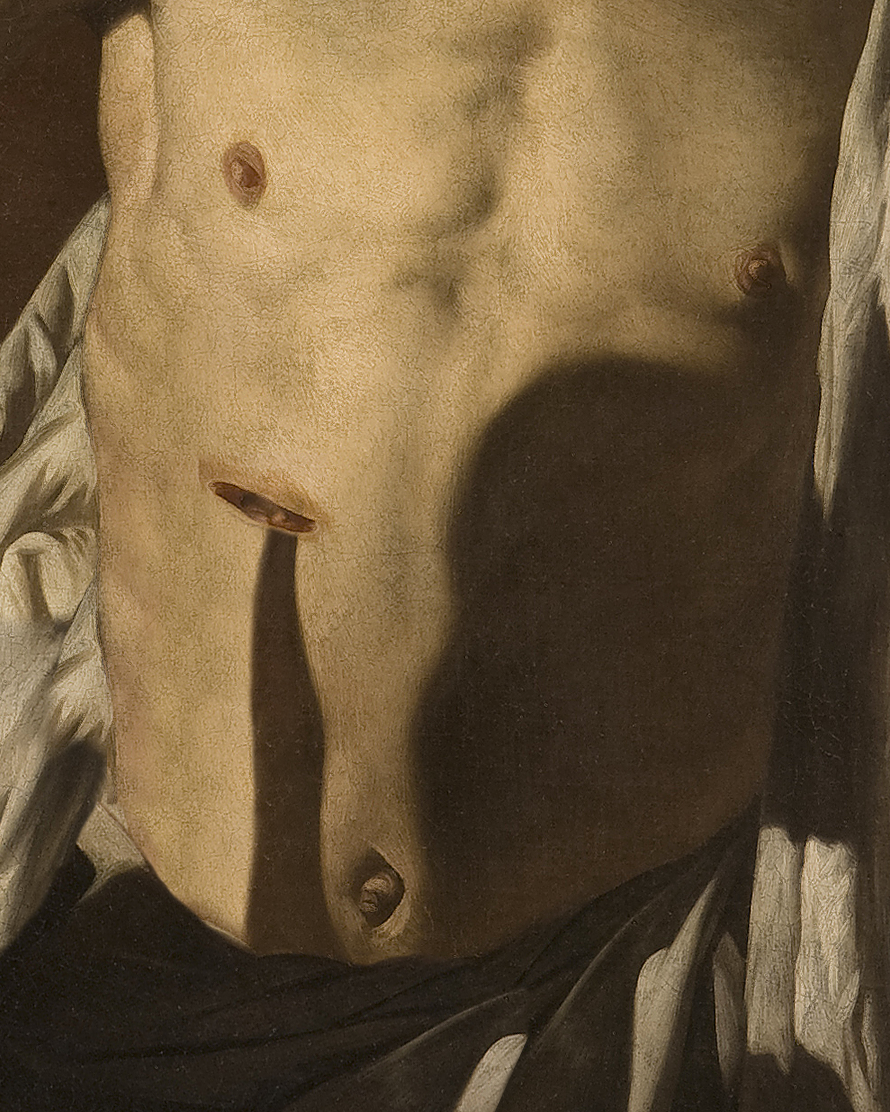

like the exact moment when the Spaniards strolled

into Tenochtitlán with their beards,

and armor,

and swords,

and horses,

and viruses.

We of Mexican mothers know that haircuts

are always banged out at home,

in the kitchen, with Glad Bag ponchos

stretched over our shoulders,

but sometimes,

if we’re lucky,

we’ll sit in the kitchen of

our favorite tía because she did a year at

cosmetology school before she had to drop out.

We of Mexican mothers are constantly reminded that

life will never be as hard for us as it was for them—

especially if we’re the sons of Mexican mothers.

We know, without ever being told, that there are sometimes

things you just don’t talk about

with your Mexican mother—

like Mexico,

or your older siblings,

or if you’re a girl,

boys,

or if you’re a boy,

boys.

We of Mexican mothers know that

when we complain of an earache,

smoky salvation will come in the form of a

rolled-up newspaper and a match.

We of Mexican mothers know that

we will only ever be as Mexican as

our Mexican mothers want us to be.

We know, because we have learned from

our Mexican mothers’ tears, that

Mexican men are dangerous and unreliable

creatures and that sometimes

a white man will have to do the trick.

We of Mexican mothers

—and white fathers—

know that our white fathers

will feel left out and become angry

cuando nuestras jefitas

nos hablan en español.

We of Mexican mothers

—and gabacho fathers—

sometimes feel it necessary to

look around and ask ourselves:

“How the fuck is this supposed to work?”

We of Mexican mothers are nothing alike, except

in that that we know how it feels

to drag an anchor, and that

we will never not be

from Mexican mothers.

Note on the Office Fridge

Dear Pendejo Who Stole My Pinche Lunch,

Are you aware that my ancestors ate the hearts of children to be closer to the gods?

Can you be so certain that I have not quietly revived that solemn ritual in my search

for meaning,

here, where we spend so…many…hours of our lives?

I will confess that I have not always been the cheeriest of colleagues.

The first to raise his hand and say, “Can do, boss!”

The best “team player,” so to speak.

But I am nothing if not devout.