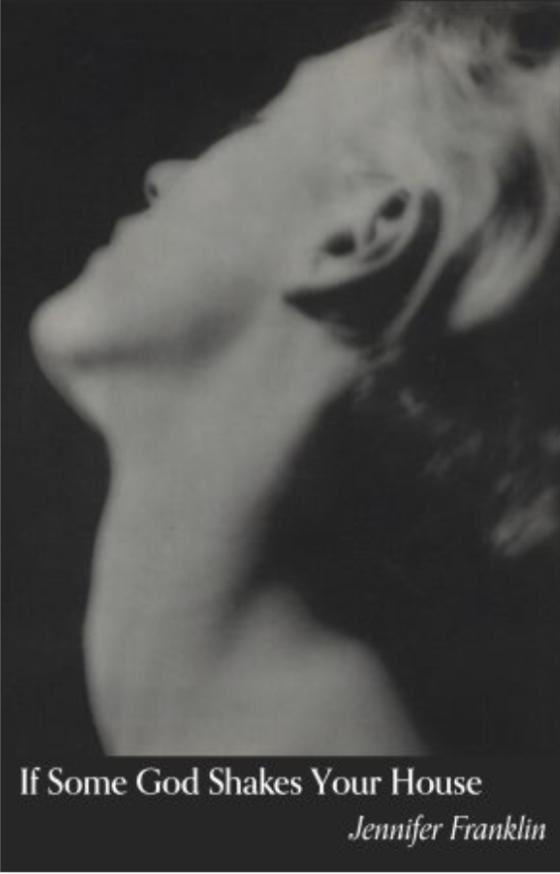

An Interview with Poet Jennifer Franklin

by Shannon Pratson

Across her three poetry collections, Jennifer Franklin not only wrestles with the question of survival but also meditates on the dignity that ought to accompany this living in an otherwise cruel world. Caretaking for her severely disabled daughter, surviving tongue cancer, enduring the pandemic in New York CIty, insisting on reproductive rights amidst political precarity—these are but a few realities Franklin navigates in her third collection, If Some God Shakes Your House (Four Way Books). No stranger to invoking Greek myth and persona poems, Franklin often inhabits the voice of Antigone. “Her conviction that she had a duty and needed to bury her brother was, for me, the same conviction that I needed to devote myself to the care of my daughter, even if it killed me,” she says.

Jennifer Franklin is the author of two previous full-length poetry collections, most recently No Small Gift (Four Way Books, 2018). Her work has been published widely in print and online, including American Poetry Review, Barrow Street, Beloit Poetry Journal, Bennington Review, Boston Review, Gettysburg Review, Guernica, JAMA, The Nation, New England Review, the Paris Review, “poem-a-day” series for the Academy of American Poets on poets.org, Prairie Schooner, and RHINO. She received a City Corps Artist Grant in poetry from NYFA and a Café Royal Cultural Foundation Grant for Literature in 2021. For the past ten years, she has taught manuscript revision at the Hudson Valley Writers Center, where she runs the reading series and serves as Program Director. She also teaches in Manhattanville’s MFA program. She lives with her husband and daughter in New York City. Her website is jenniferfranklinpoet.com.

*****

Shannon Pratson: There are so many places our conversation could begin. I am a bit hesitant to begin with death. But death feels unshakably present within the collection. The book begins with a gesture towards death, in the lines by Louise Glück, “death cannot harm me / more than you have harmed me, / my beloved life.” And then again, with the first poem, “How you wouldn’t accept / they were dead.” There are ample gestures in other poems, too. And, of course, Antigone’s story is grounded in death—in her courage to bury her brother, to look death in the eye. But, perhaps most explicitly, death is present in the Memento Mori poems. And I was wondering if we could begin there. Could you talk a bit about the role memento mori plays in the collection and, more broadly, your work as a poet?

Jennifer Franklin: I am glad that you want to begin with a discussion of death and the crucial importance it plays in this collection as well as the importance it plays in the original story of Antigone.

For at least half of my life, I have believed that there are things that human beings suffer that are worse than death—conditions like prolonged torture or not having any autonomy over one’s life. At the same time, I believe that one cannot say with any certainty what one would do in a hypothetical situation. Eleven years ago, I had tongue cancer and had to have a partial glossectomy, all the lymph nodes on the left side of my neck removed, and seven weeks of radiation. When I was finally properly diagnosed, it was unclear if I would survive more than a few years. During my treatment, I underwent a surprising transformation. I both came to terms with my mortality and fell deeply in love with my life, despite all its challenges and tragedies. When I was diagnosed, my profoundly disabled daughter was eleven years old. I was a single mother and without childcare assistance or a job outside the home. I had to rely on my parents to help me take care of my daughter while I spent hours a day in the hospital getting my treatment. I had to envision my daughter’s future and make a lot of difficult decisions. I found that when I truly “looked death in the eye,” it made me appreciate life much more.

The memento mori sonnets were written in concert with the Antigone persona poems. I discovered that meditating on Antigone’s acceptance of her own death made me see death everywhere I looked. When I entered remission, I felt that I was given a new life, a reprieve from the clutches of the Grim Reaper. The last line of one of the poems I memorized to recite in the radiation room was now with me all the time—Rilke’s “you must change your life.” It wasn’t until I understood, as more than an abstraction, that everything alive must die, was I able to be truly present in a deliberate way. A way that did justice not only to taking care of my daughter or devoting more time to my writing but to taking better care of myself and all my relationships.

When the speaker of the memento mori sonnets is reminded, “remember you will die,” she is able to recalibrate and embrace her life with all its flaws and all its tragic dimensions, both personal and global—illness, loss, democracy in peril, multiple wars and conflicts, the climate crisis. Louise Glück has been one of my greatest inspirations throughout my writing career so it made sense for my Antigone to begin with one of my favorite moments in her work. This book examines a lot of difficult subjects with honesty but I think there is a lot of hope in these poems as well. The importance of art and art-making is central to the book. The balm of art and love are what keeps the speaker engaged with life, despite her isolation from caregiving. Toni Morrison wrote, “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

SP: You have written and spoken about Antigone and your reasons for using her as a persona. So my question is less about why and more about how. In writing this book, how did you tap into Antigone in your writing process? Did you have a ritual? Any lines you kept close? Anything at all that might be generative to other poets seeking to commune with figures and voices from the past.

JF: Yes, I have spoken a lot about reading Antigone by Sophocles as well as Antigone by Jean Anouilh for the first time in AP English and knew that I wanted to write about her at some point.

I didn’t feel I was ready, emotionally or psychologically, until I had a third of my tongue removed, a temporary tracheostomy, seven weeks of radiation, permanent damage to my jaw and painful side effects that I live with every day. Many people have experienced bargaining as one of the stages of grief. When I thought I was going to die, I accepted that fate as long as I could be assured that my daughter would be safe and cared for. Since then, I have dreamed that eventually she would be accepted to live full-time at an organic farm in upstate New York.

My fierce obsession with her well-being was the well from which I drew Antigone’s passion. Her conviction that she had a duty and needed to bury her brother was, for me, the same conviction that I needed to devote myself to the care of my daughter, even if it killed me. I read as many translations of Antigone as I could find. I immersed myself in all the representations of Antigone that I could find—the hubris and humanity of Anne Carson’s Antigonick, the political passion of Seamus Heaney’s The Burial at Thebes, and Anouilh’s Antigone with her love for her memorable little dog, all made an impression on me. I also read critical essays on Antigone and watched Juliette Bioiche’s incredible heart-wrenching performance. I have always loved writing persona poems. When I was young, the poets I loved most—Sylvia Plath, Louise Glück, Rita Dove, Laurie Sheck as well as my graduate school mentors—Richard Howard and Lucie Brock-Broido—wrote and taught me many of the most brilliant persona poems ever written.

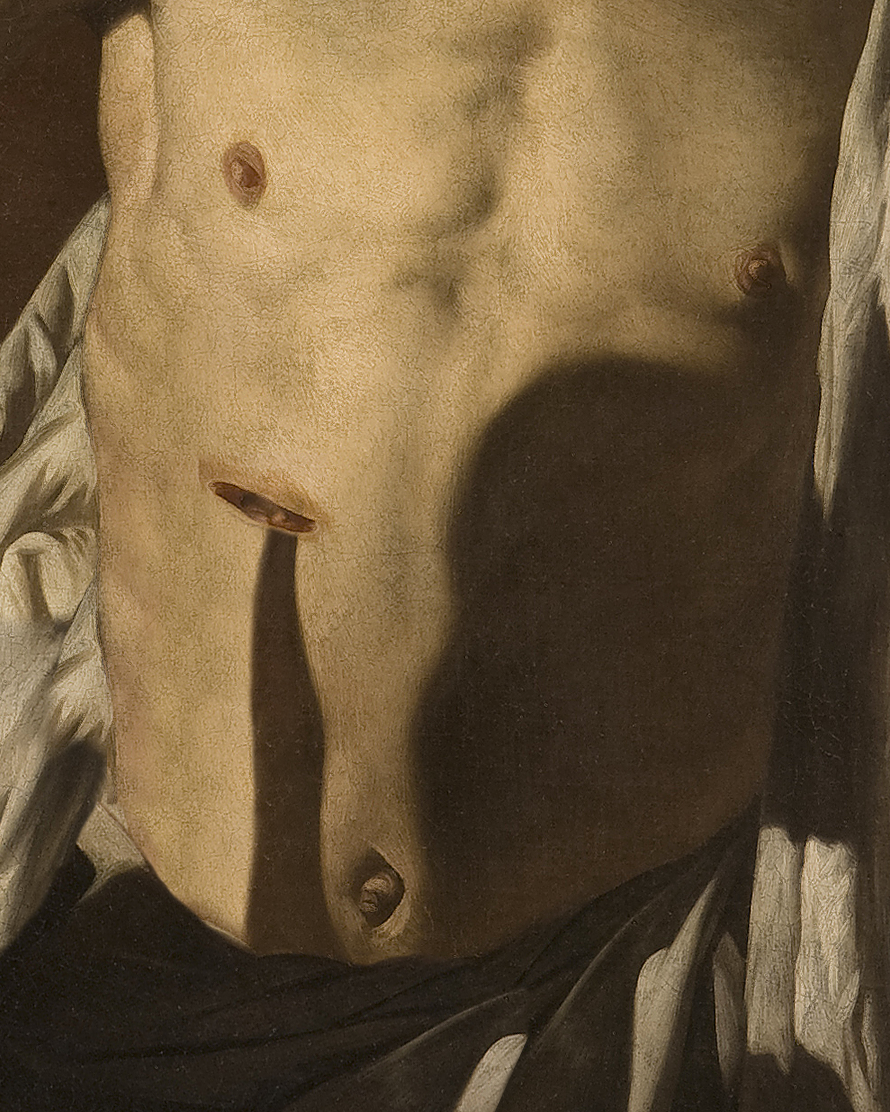

It is easiest for me to delve deepest into emotional truths when I wear the persona of a character—most often from Greek mythology but sometimes from modernist or art. The central poems of my first book, Looming, grapple with my daughter’s diagnosis in a series of poems in the voice of Demeter, the grief-stricken mother of Greek myth. The book also has a suite of poems in the imagined voice of Penelope and characters from Faulkner, Ibsen, and Joyce as well as a series of poems called “In Father’s House” which are in the imagined voice of women writers who lived, as adults, in their childhood homes—Emily Dickinson, Emily Brontë, Virginia Woolf. In my second collection, No Small Gift, I embody the persona of Philomela to tackle abuse, betrayal, and tongue cancer. The poems that feel most intimate and authentic are my persona poems. Whenever I am at a loss for a subject, I turn to ekphrasis.

SP: You have written about how Antigone became a kind of “Jungian shadow figure” for you when you were young. I am so compelled by the idea of the “shadow figure,” particularly in the context of poetry. I believe collections have many shadow figures—the art, people, and ideas that cluster around the work, directly or indirectly. Are there any other shadow figures that cluster around this collection? Perhaps another way to ask this question would be, what was the art you kept company with while you were writing this book? The books on your nightstand. The movies and/or media you were consuming. The music in your earbuds.

JF: Yes, I considered Antigone my first Jungian shadow figure because she represented parts of myself that I couldn’t access at the time but wanted to. I admired but was also afraid of Antigone’s bravery. As a sixteen year old who had never been tested by tragedy, I wanted to believe that if given the chance I would do what I felt was morally right but I didn’t know if I would have the courage to act on my convictions.

The same semester that I was reading Antigone, I discovered the music of Sinéad O’Connor. She was another shadow figure. The rebellious, tough but vulnerable young woman with the voice of an angel. My biggest teenage rebellion was blasting her music on my stereo. At the same time, we were studying the Holocaust in AP History. I was obsessed with Miep Gies, who hid Anne Frank and her family in the annex for 25 months before they were discovered, deported to concentration camps, and murdered (except for Otto Frank). I used to ask myself, would I have the courage to do what Miep did? I hoped so. These were the character traits I wanted more than anything—bravery, conviction, fierce loyalty. I don’t think I embodied these characteristics when I was young but I have grown into them.

I certainly engaged with art while writing If Some God Shakes Your House. Other than the translations of and essays about Antigone, I was reading a lot of Louise Glück, because I am always reading Louise Glück. I saw several productions of Beckett including an Irish production of Waiting for Godot at Lincoln Center, Beckett’s Women in the City, and a one man show with Bill Irwin. Beckett’s world view insinuates itself into a lot of my work. About half of the book was written during the pandemic when my family observed strict lockdown (because of my daughter’s epilepsy and my compromised immune system) in NYC before the vaccines became available. The last day we went to work and school was Friday, March 6th. My daughter began school again in mid- April 2021. I read a lot of news during quarantine and the anxiety from living during the Trump administration informed a lot of the prose poems. Never before had my work been so political. Several memento mori sonnets were provoked by pieces in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and art magazines.

I became interested in the art of Cy Twombly and Ana Mendieta. I was reading about the abuse she suffered at the hands of her husband, Carl Andre. (Since the book was completed, I heard an incredible podcast, Death of an Artist, about the murder trial of Andre and the way the men of the art community protected him.) I was looking at a lot of art by Louise Bourgeois. In fact, the original cover I considered for the book was a sculpture by Bourgeois I Redo from the 3-part installation, I Do, I Undo, I Redo because it truly got to the crux of the fact that my daughter and I have never been allowed to fully separate from each other. Though she may not be attached to me by an umbilical cord, she is a toddler in a twenty-three-year-old’s body and still grabs my breasts and asks me for “milk.” I still have to get on the floor and bathe her every night and sing her Sesame Street songs before bed. It’s something that makes people uncomfortable to witness—the tragedy of her lack of autonomy and agency. Her complete vulnerability and inability to care for even basic self-care without significant assistance. Bourgeois’ piece speaks to the way the burdens and responsibilities of motherhood are lifelong.

SP: In an essay, you write “I was like Antigone, in love with the impossible, and I had to accept that I would invariably sacrifice myself—my health, my time, my career—to do what needed to be done to keep [my daughter] safe and to teach her as much as possible so she could eventually have enough skills to survive in the world when I was too sick or old to take care of her.” Sacrifice feels like a taboo subject in the artmaking world—but particularly in the writing world. I think there’s this toxic idea that art and writing get made by people who are unencumbered by responsibility and sacrifice. And yet, this feels to be such a limiting and exclusive belief. When I think about it, my favorite art and writing has been made by people who are profoundly and unshakably entangled with others. I am wondering if you could speak to the entanglement of sacrifice and writing.

JF: This is a really important question to me and I agree with you that there seems to be a taboo in the writing world about the subject of artmaking by women who are caretakers, especially caretakers of the disabled or the elderly. While a lot of recent reviews I have read have praised men for writing sensitively about the trials and tribulations of parenting, it seems as though there is a backlash towards nuanced collections by women that directly address darker aspects of parenting such as postpartum depression, abortion, disability, and aging—cancer, divorce, cobbling together several jobs to make a living—real life problems that are not traditionally associated with poetry. I recently read a profile of a novelist where the writer claims to read 300 books a year and writes a draft of her book and puts it in the drawer and doesn’t look at it while revising the next draft. That’s not the kind of writer I am. I write in the middle of the night when my husband, daughter and dog are sleeping and when I finally stop answering emails for my day job as Program Director of the Hudson Valley Writers Center. Most of my friends and students who write don’t have the luxury of writing as their full-time job. They write in interstitial moments between fulfilling all their other responsibilities. One of my closest friends is a full-time caretaker of his wife who has Parkinson’s Disease. The students I am most proud to mentor are those who have dreamed of publishing a book since they were teen-agers but life became so complicated and demanding that they finally returned to writing during retirement. These are poets who are writing about the brutality of life and they are strong enough to see the beauty too and to sing about it.

SP: You write so beautifully about Antigone in a modern context. Antigone waiting for biopsy results. Antigone walking the treadmill. I wondered if we could end there. Where is Antigone now? What are the places she haunts? What is she doing? What is in her pockets? What does she love? What makes her weep? What makes her laugh?

JF: Antigone, first and foremost, is hoping that there is not a second Trump Presidency. She is in the group of historians and scholars who believe that our democracy will not survive another four years of his reign. She is trying very hard to exercise five days a week and get to the bottom of her chronic cough and other health problems brought on by caretaking 24/7 for a disabled adult and holding down a full-time job. She spends her free time at art exhibits in NYC and just returned from a pilgrimage to Keats’s house in Hampstead Heath where he wrote most of his poems and shared a house with Fanny Brawne and her family. She has Purell and honey cough drops in her pockets and worry dolls on her nightstand—one for each of her family members, including her nine year old rescue pitbull, Dottie.

I am writing a new book of poetry called A FIRE IN HER BRAIN about Lucia Joyce and other erased and silenced women who were deemed “mad” but I argue were institutionalized because of misogyny. I love shelter dogs (shoutout to Cole the Deaf Pitbull, Sheeba, and Snoopy), British crime and spy shows, hot baths, and listening to playlists my husband recorded where he reads me his favorite poems. I weep for the thousands of innocent people killed in all our current wars, and all the women and girls who are victims of sexual violence. Susan Sontag wrote that “someone who continues to feel disillusioned when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood.” Just when I think I cannot be surprised at the depravity human beings can sink to, I am confronted with more horrific examples. I am privileged to have a loving family, my teaching, and my writing. And a pile of books on my nightstand—Microliths They Are, Little Stones, Posthumous Prose by Paul Celan, Michael Cunningham’s new novel, Day, The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez, The Hundred Waters by Lauren Acampora, The History of Art without Men, and an ARC of Modern Poetry by Diane Seuss. These are the things that are bringing me joy in our burning world.