Spring 2023 Editors’ Note

By Florence Gonsalves and Amanda Hodes

Welcome to the Spring 2023 issue of The New River: A Journal of Digital Art & Literature. Since 1996, The New River has sustained its reputation as one of the longest-running journals devoted to electronic literature and digital art. With the development of new technologies, artistic mediums, and aesthetic trends, The New River has adapted stylistically to feature dynamic works that prompt reflection on the world today. The Spring 2023 issue continues this commitment to inquisitive play with a collection of nine interactive and expansive pieces that implicate the user with a tactile, kinetic, and material approach to language. To experience this collection is to consider the stakes of our changing human predicament by engaging with various translations–of texts to kinetic screen, of language to another language, of human to bot and back again.

When we considered these pieces in conversation with one another, fields of inquiry emerged around these three categories:

1) human labor and the workforce

2) beauty, aging and gender

3) relationships to authorship and language

Innovative and brazen, the Spring 2023 issue celebrates the works of Ivan Zhao; José Aburto; Dahlia Bloomstone; Terhi Marttila; Anni Garza Lau; Faith Bassey and Deena Larsen; Scott Rettberg; Jon Stone; and ¡wénrán zhào!.

Please note that some of the works in this issue are best experienced on a desktop or laptop computer (rather than on a smartphone).

* * *

Human Labor and the Workforce

Many of these pieces engage to various degrees with the volatility of the labor force and the urgency of sustaining oneself in a changing marketplace – changes that have to do with the influx of tools such as ChatGPT that, on the one hand, open up human possibility for creation by making works like Lecsicon possible, but also beg the question: Is human labor becoming obsolete? How interchangeable are “we”? How human even is human labor?

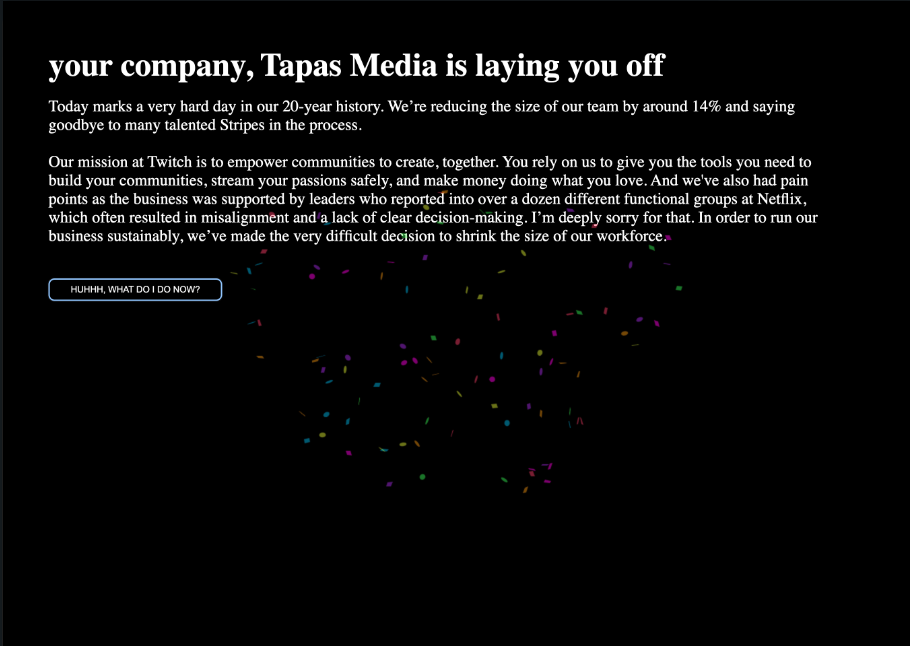

In “YOU JUST GOT LAID OFF!”, the user is hit with a header that informs them of their lay off status from X tech company. The company names are randomly generated in each reader’s experience and are cycled through quickly, with Zipcar becoming Terminus becoming Loft. The piece then generates a generic termination letter, taking lines from major corporations which interweave together to create something that is parseable, but reflects the lack of thought and empathy put into layoff letters. By clicking “Huhhh, what do I do now?” confetti explodes, and a new sentence of the lay-off letter is revealed – heartfelt, uniform, and generated by AI, with the details of the letter as applicable to a major clothing store as a rideshare company. This piece was a response to Zhao’s own experience working in tech. He writes, “Given the timing, the wording, and the percentage of people who were laid off, it felt suspiciously similar across the board. All of these decisions and letters felt impersonal, devoid of human consciousness, and questions the relationships between individuals and their employers.”

Cafeína speaks to the unease of staying relevant in a changing human workforce. To experience Cafeína, the user starts with an empty cup and fills it with possible variations of milk, coffee, and water. If everything we consume digitally and physically is translated in the body to reflect a much more complex societal mechanism, what does it mean to be stimulated? Aburto explains, “Each ingredient has been resignified with a verse, but all the poems have the same end: ‘you must stay alert.’” Every coffee iteration then comes back to the imperative of staying vigilant, but what does “alert” mean in our current landscape? Awake? Awake for whom? Or for what? As the zeitgeist urges, be productive, be worthy, and make a contribution. As such, another trend that emerged alongside human labor and the workforce was one of value, and how the work one does is appreciated and awarded (or not).

The haunting last stanza of Cafeína’s translation reads, “Remember, that Life and its delights / can leave you behind / at any time / you must stay alert.” In other pieces throughout this collection, the threat of being left behind is palpable, though the reasons for becoming obsolete vary, especially by industry. Whether in sex work or tech, ours is a society obsessed with stimulation, stress, and competition. And cash…

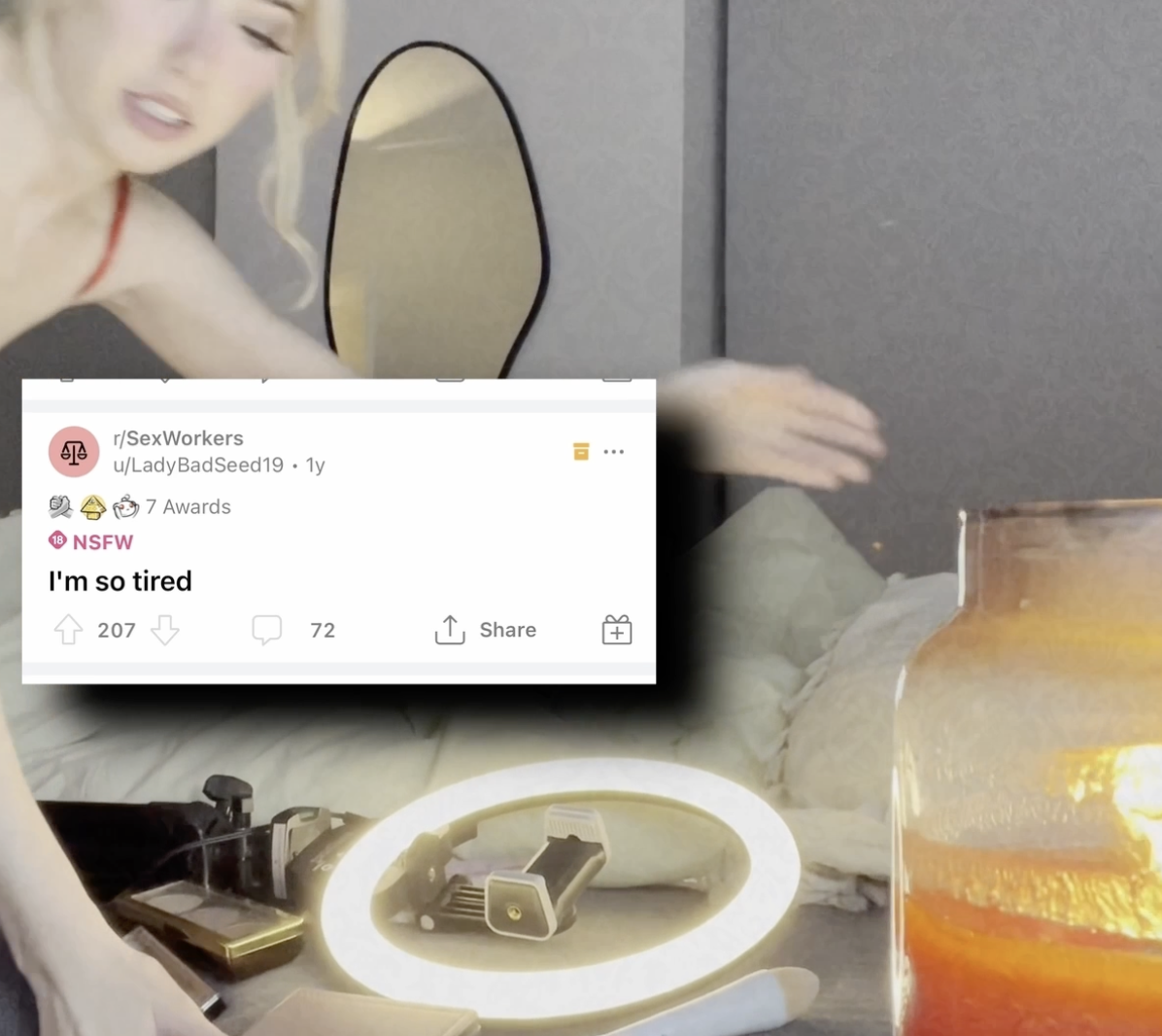

The virtual and IRL are woven together in three acts in Dahlia Bloomstone’s Didactic Mergers, Things r Happening, We r Aging and Here, as the character processes aging in the sex work industry. Sonically, the piece echoes, bubbles, and cha-chings, as various voices and perspectives compete with one another and themselves to express disdain for those in the trade. In the second act, surrounded by a glow ring, makeup products, and cameras, the speaker tries to express what’s making her “the most sad right now,” but is interrupted by the sound of cash, her own inquiry repeating on loop, and eventually a layered answer amidst pop ups of Reddit posts. As the user experiences Bloomstone’s work, it is not only her labor and its value that is questioned, but also the long term viability of her career given the precarity of female beauty standards. When the character describes her mom’s shared Amazon Prime account full of anti-aging products, beauty creams, and collagen gummies, there’s also a subtle acknowledgment of how gendered pressures around beauty and aging are passed down generation by generation, from mother to daughter.

* * *

Beauty, Aging and Gender

Terhi Marttila capitalizes on this inherited pressure in a way that implicates the user upon first click in Gray Hairs. In this interactive poem the user faces a screen of small black dots, representing hairs, and is instructed to wait for the first gray. After a few seconds of anticipation that feel reminiscent of waiting for one’s own first sign of aging, the black circles begin to lighten, gradually fading and becoming invisible. To “avoid” the graying process and evade invisibility, the user can click a gray circle. Doing so turns the hair black again, restoring the user to relevance, and also displays a fragment of the poem spoken in the artist’s voice. Although confessional and told in the first person, the exigence behind Gray Hairs surpasses the individual. When Marttila speaks, her “I” represents a common pressure and prevalent obsession that disproportionately impacts women to not only dye and pluck their silvers, but to hide other signs of aging. Clicking the gray hairs isn’t optional if the user wants to participate. Similarly, given societal pressures and standards of beauty, women are often scrutinized for aging “naturally.” They are expected to do something about it, usually at a cost, whether through the time and energy of altering their hair color, or spending money on products meant to counter the inevitable, as was seen in Bloomstone’s piece.

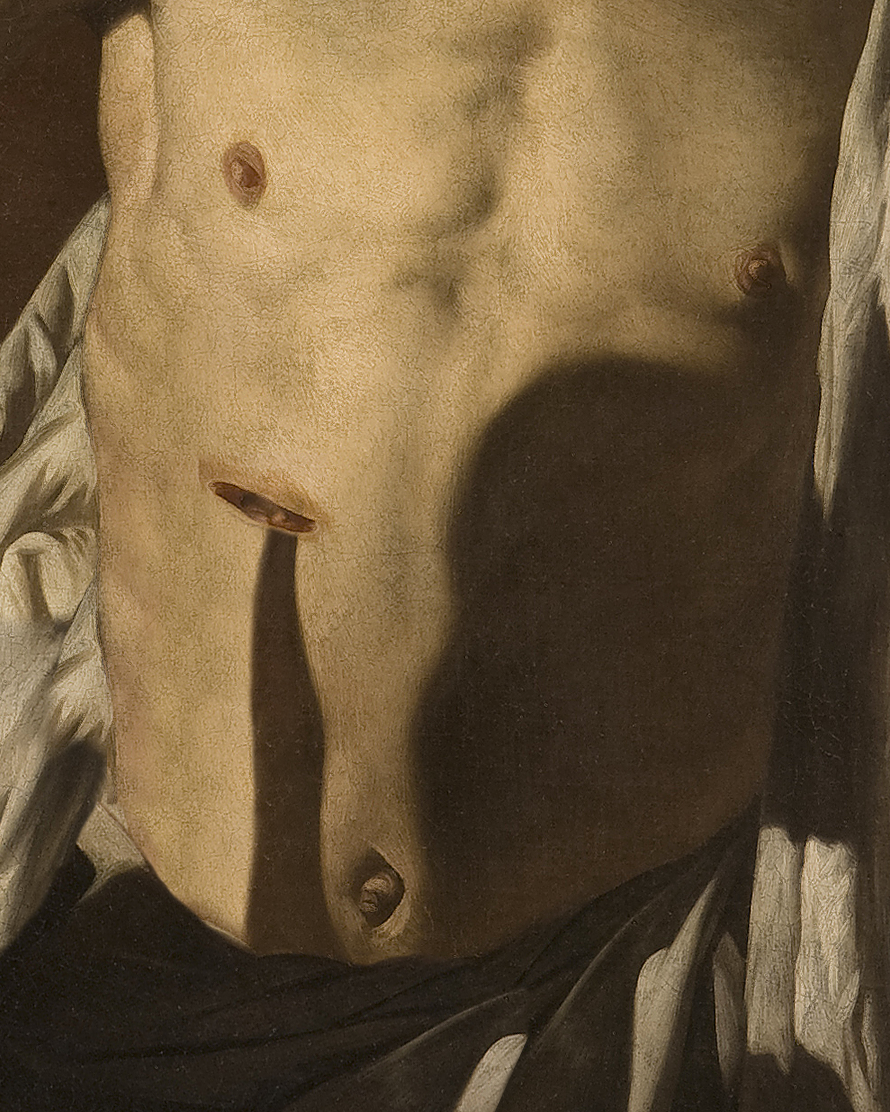

To engage with beauty and aging via Bloomstone and Marttila is to acknowledge the gendered lens through which women are perceived by society, with the danger of their experiences increasing greatly depending on the cultural landscape. In Anni Garza Lau’s Fading, using simple mouse gestures to interact with abstract shapes, the reader experiences a woman in the last moments of her life, collecting her thoughts and memories. The main character feels like “a piece of meat about to collapse” and lists an indifferent government, as well as people with absurd beliefs for her predicament. Lau explains, “Through a subtly immersive experience, the piece addresses one of the most important and neglected issues of Mexican society: femicide.” In the end, Fading takes the user through a variation of what too many women endure–and the weight of what gets carried inside.

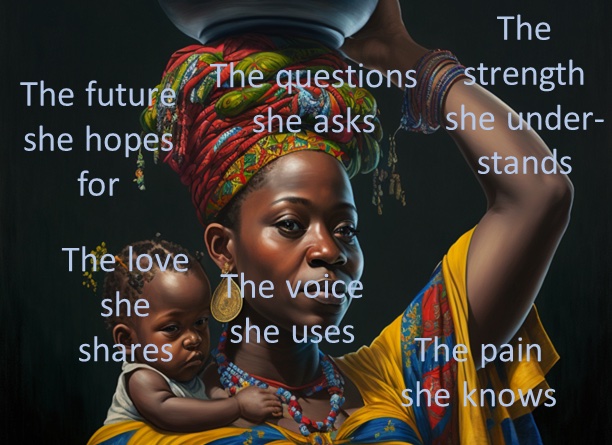

Gendured endurance continues in “The Water Seller (Mai Ruwa),” which uses memory in a similar fashion and takes us back to 1988 in Obodo, Nigeria. The piece opens on an image of Aiwa, a water seller, who carefully balances the water on her head in a curved water pot, hearing the familiar slosh and taking on the daily weight yet again. She also carries a child. At a time between the old and the new – when computers and cell phones were only just becoming available for the government and elite – Aiwa remembers her past and looks toward her future. The storyline consists of eight threads, including “The body she cherishes” and “The pain she knows,” which bring the user back to Aiwa’s lived experience and the societal implications of her labor given the emerging tech industry of the time.

* * *

Relationships to Authorship and Language

Considering romantic relationships throughout history, Scott Rettberg turns his attention to affairs of the 19th and 20th century. In The Love Letters Suite, Rettberg draws from correspondence by literary and computational authors, such as Simone de Beauvoir, Henry Miller, Oscar Wilde, and Alan Turing. The four works consist entirely of texts by these authors, and Rettberg was also assisted by ChatGPT in creating the code, engaging in what he terms “cyborg authorship.” In this way, The Love Letters Suite has been collaboratively developed with the historical authors, large language model, and Rettberg himself. It takes relationships not only as its subject matter, but also as its form, prompting us to reflect on collaboration and authorship in the present day.

“I could kiss, say,” considers the Western relationship to the global environment. In this “ludokinetic” poem, the interface of the mouse and cursor becomes a physical medium for intervention in the text. We “kiss” the language; we click the quotation mark up to reveal this ecological poetry. Through kinetic poetic language, we reach closer to the nonverbal embodiment of the ecological and nonhuman. Moreover, Stone elaborates, “In playing through [the poem], you don’t merely explore or encounter the poem but enact it. You are an anticipated feature of it.” This echoes back to The Love Letters Suite, prompting us to reconsider the relationship between authorship and text, reader and interface.

In the language game Lecsicon, ¡wénrán zhào! created a prompt for GPT 3.5 Turbo, the large language model utilized for ChatGPT. This unfolds a word as an acrostic in sentence form, with the sentence appearing letter by letter. For example, the user might come across the word “Dime,” and the sentence typed out is “Diving Into My Emotions.” “Dime” brings to mind money, currency, finances, exchanges, and coins, but the generated sentence implies something deeply heartfelt. This juxtaposition – one of deep emotion versus a ten cent transaction – opens up language and creates new avenues for meaning-making. To engage with Lecsicon is to upend the readers’ implicit relationship with language at the level of a word. As the letters accumulate into sentences, users witness how an altered context slowly emerges and triggers new lingual associations. The sentences that emerge aren’t constrained by meaning. Rather, the goal, as ¡wénrán zhào! so eloquently puts it is to “flesh out how the units of meaning (letter, word, sentence, paragraph) feed into each other and meaning bleeds through the edges.”

* * *

Thank you to Shiven Saxena, Jay Culmone, Fez Fessenden, Shaheer Malik, and James O’Brien for their editorial assistance. We also thank Virginia Tech for its continued support of the journal over the years, and we are grateful for the writers and artists who trust us with their groundbreaking work.