An Interview with The HTML Review Founders:

Maxwell Neely-Cohen and Shelby Wilson

by Kaitlyn Grube

Editor, Kaitlyn Grube sits down with the founders of HTML Review to discuss e-literature, online journals, and A.I.

*****

KAITLYN GRUBE: Hello Shelby and Max! I’m so glad you guys could chat with me today. How are you?

SHELBY WILSON: Great! Thanks so much for having us.

MAXWELL NEELY-COHEN: Yeah. Its great to be here.

KG: All right. So, how about you guys tell me a bit about yourselves—who are you, what do you do, that kind of thing.

M N-C: I’m Max Neely-Cohen. I am a writer, an editor, but I’ve also spent a lot of time not doing those things. I’ve worked in theater, dance, technology, video games, film sometimes, all sorts of fun stuff.

SW: And I’m Shelby Wilson. I’m a software engineer by trade. I make a lot of web interfaces and data visualization. Then I also have a creative practice in new media and digital art.

KG: And how do you define e-literature or e-lit for short?

M N-C: I mean, the honest answer is, I kind of don’t (laughs) is what I would say. I mean, I think for me, I kind of just think of everything as literature and then think very specifically about the medium in which that literature is living. Down to even the differences between, like, a codex and a scroll versus something like the World Wide Web. So that’s kind of how I think about those distinctions, but I’m the type of person where I’m like, everything is the same (laughs) which can be very annoying. But it’s just kind of how I think about it.

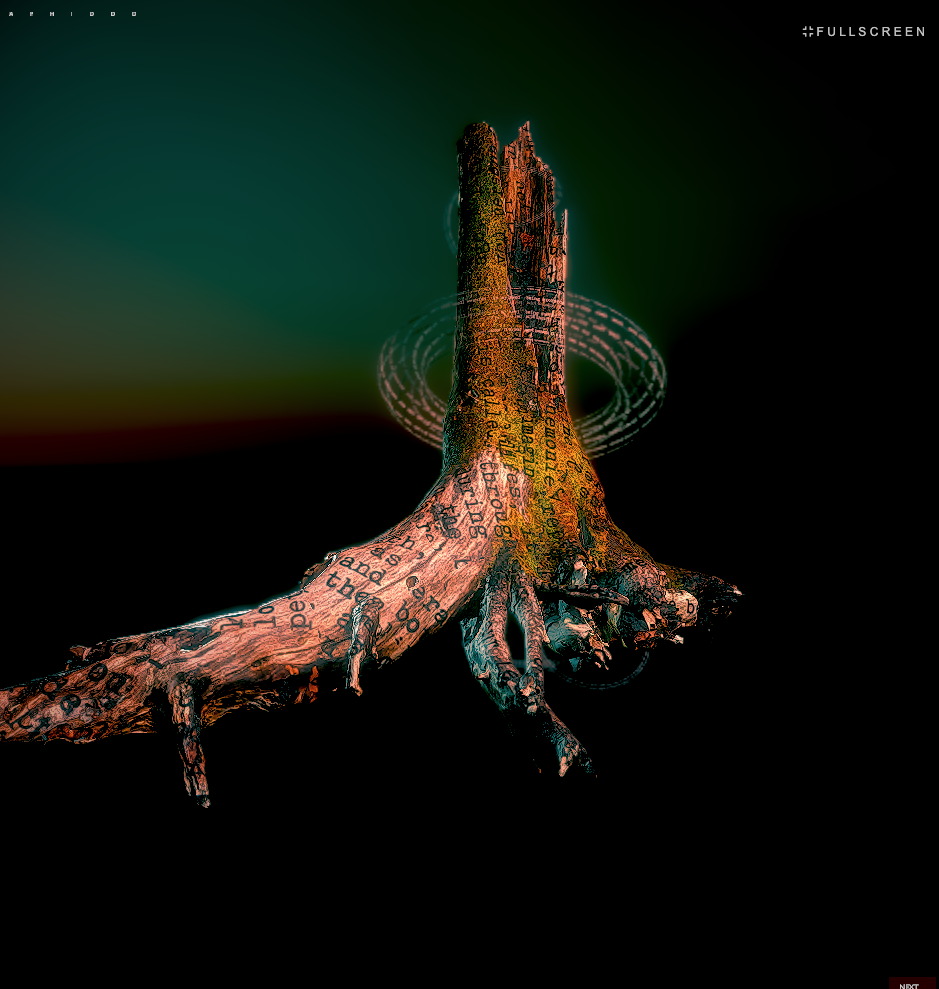

SW: Yeah, I think it’s…it can be very broad. With The HTML Review, you know, we say it’s literature that’s made to exist on the web, and that’s kind of like the foundation of it, but it can also extend to lots of different iterations and versions of literature. It kind of blurs the line between website, literature, art.

KG: Would you say that mostly it’s the medium that separates it or are there functions of the form and the ways that it presents that are different than regular literature?

SW: Yeah, totally. There are all these affordances with e-literature. You can play with, you know, duration and pace of how you’re consuming or reading the piece. Animation, you can play with the browser itself, too, and links within hypertext. So I think it’s very much about the medium.

M N-C: Yeah. I mean, I think it’s also like—it’s really interesting—the ways in which different platforms or approaches can cause even these unanticipated constraints, and I think that’s where like a lot of really incredible work comes from. Even sometimes unconsciously.

KG: Yeah. Can you give me an example?

M N-C: You know, there’s been a few times where—and I’ve had this experience as a creator, but I’ve also seen it as an editor—where there’s a huge difference between how a piece existed in a writer’s brain at the beginning and how they imagined it would look or feel or interact or exist. And then the medium imposed constraints or challenges, but in ways that I actually think end up often helping the piece.

KG: Can you guys tell me a bit about The HTML Review and what sets it apart from other literary journals in the field?

SW: As I said before, I think we kind of blur the line between website and literature and art. But we do follow like a somewhat traditional publishing model. So we have, like, an editorial cycle. We have an open call for pieces. But it’s quite experimental, and contributors have control over all of the code that we publish, although we offer support, of course, and, you know, can help them develop a piece. But they’re also free to host their own pieces. So we can host it for them or, you know, we can link out to the piece that they host.

M N-C: That’s the one part of our approach that I do think is very different, is we really—as we were sort of starting it and figuring it out—drilled down on, okay, what is the nature the web? And why are we sort of using this medium? And one of the things about the web is: a single entity doesn’t have to host everything. And concepts of ownership are a little different than how they work in other situations, and so we’ve decided to embrace that, which is weird and changes things a little bit. But so far it’s working. It’s working for us. And I think it also, in a way, our role…yes, we are sort of “publishing” these things and we’re going through an editorial process with writers and sort of helping them figure out the best version of the piece. But at the same time, we almost act as like…an incubator or supporter of new work. Like an opportunity to do something you might not.

KG: Yeah, totally.

SW: We really encourage our contributors to, like, play with the new medium or work outside of something that they’ve already done or just, you know, encourage them to be very experimental.

KG: What made you decide to start a literary journal?

M N-C: So Shelby and I met. We were part of the same cohort at this New York institution slash thing called The School for Poetic Computation and we…I don’t know, we were kind of talking about these ideas in a very abstract sense while we were there, a few times and in different ways. And I think for me, it was…I was surrounded by all these incredible artists and writers and creators of digital media and I was kind of dissatisfied with, like, the formats in which their work could be disseminated or displayed. For me, as someone coming from the literary world, I was like, “Oh. What if we just, like, used the model of a literary magazine for this sort of work?” And that was—at least for me—what inspired it.

SW: And I was coming from this creative coding world and using code in a creative way and I was, you know, thinking less specifically about literary magazines until I talked to Max (laughs) and this became, like, a possibility. But when we started, Max called me one day and was like, “I bought a URL. I want to start this. I have this idea to start something called The HTML Review.” So that was, yeah, that was the beginning of it.

KG: So this was kind of a surprise on your end. He just showed up and was like, “I did a thing!”

SW: It was like, “I had this fun idea for a project. Let’s try it out.” And the first one, you know, it really was—we didn’t know where it would go. The first issue was, you know, it could have just been one issue. But it’s great that it’s continued and become this annual thing.

KG: That’s awesome. I love that. Can you tell me about a time that a piece of e-lit moved or inspired you?

M N-C: It’s funny because, growing up, I have these memories of seeing a few anonymous works of hyperlinked web poetry or web art that I just loved (laughs) loved to death. And what was interesting about all of them is that none of them were signed. They were all just sort of these, like, strange artifacts that now I’m convinced are surely lost. That got to me by whatever weird vector being a, I don’t know, middle school kid who had taste in weird music. I ended up sort of sometimes seeing these other things. And then later, you know, there was a lot of stuff like the work of Jody [Zellen], the web art collective, and then, much later, Allison Parrish has always been a huge inspiration. And Allison’s compass poems just move me every time.

KG: Tell me more about the compass poems. What is it about them that really moved you?

M N-C: I think…they, at least for me, kind of revealed how I think about the bridge between the visual or functional aesthetic of type and graphic design and the type of meaning that can impart. And then into sort of poetry and literature—this world that I inhabit a lot. And then also there’s this technical and technological element that I’m personally fluent in. So in this very small amount of space, my favorite one is this literal diamond shape. It’s this condensed form where it feels a little bit like how my brain feels sometimes (laughs) I guess is the best way I can put it.

SW: There was a piece that was published in The Believer in 2021 called “Ghosts.” It’s by Vauhini Vara. And it’s this conversation that she’s having with GPT-3, so it was pre- this new wave of A.I. and generative text, but it’s this navigation of grief and using the model to talk through how she feels about her sister’s death. But it’s also about anxiety around A.I. and I think it was the first introduction I had to using A.I. in this creative way—in this, like, conversational way. You can see how it evolves through the piece. At the beginning, she gives it less, so it gives her less. I don’t know. It was just this really beautiful exploration of it, and I think it really stuck with me.

KG: Interesting. Yeah, when I reached out to you guys, you mentioned that The New River was an inspiration for you when you made The HTML Review. Can you tell me a bit more about that?

M N-C: Yeah. I mean, I…it’s funny because for a really long time, even late in high school and then in college, I—from afar, probably like once a year—I would check in on this world, even though I wasn’t yet creating anything in it or doing anything in it actively. And during that time, The New River was just one of the few things I knew about that really was existing sort of in a publishing context and in a sort of gathering work and putting it out together context. And I never forgot that. And then, you know, many many many years later, when Shelby and I were starting this up, it was definitely one of the things I was thinking about because I just had so few example (laughs). But what’s so interesting about is it’s definitely the really early years of it that were most present in my mind.

KG: So we’re talking, like, ‘90s era, early 2000s. Is that kind of the timeframe?

M N-C: Yeah. Yep. It was just really valuable to know that there are others who’ve been interested in similar things, especially for a long time. I mean, we have (laughs) it’s totally corny, but we have on The HTML Review’s website this long list of friends and inspirations.

SW: It keeps growing, too, which is really encouraging (laughs).

KG: How did you stumble across The New River in the first place?

M N-C: It’s interesting. It was a friend who was sort of more aware of what was going on in this space who had been into some web art stuff, and then she sent me a very—it must have been so early. And later, the second time, it was actually a fellow student of mine in college who was like, “Oh, check this out.”

KG: What are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in running your own e-lit magazine?

SW AND M N-C: (copious amounts of giggling)

KG: I see you both laughing. I’m thinking this is going to be a good answer.

SW: I was just thinking. One of the problems we have every time we publish is choosing. We have this, like, amazing selection of pieces that we can choose from and it’s really hard to make a decision about who to publish because there are so many good pieces. So that’s one challenge.

M N-C: We’ve definitely gotten to the point where we have multiple worthy submissions’ worth of content and we’re having to just make crappy decisions (laughs) so that’s a challenge. I mean, I also think it’s been a real long-term challenge for us figuring out what type of work we are the most helpful platform for. At the beginning, I think we experimented with a lot of different formats or typologies or even just orientations and kind of learned, oh, these are the things that we really do seem to help the author and are a really good platform and community for them. And in other cases, we have less of an impact, I guess I would say, and we’ve learned how to narrow that effectively.

KG: What’s your stance on that now? What kind of things do you feel like you can best offer a platform for?

M N-C: I think there’s a few different directions. One is, I think we’re a really good platform for works that use the web as a medium or a technology really intelligently but are not about the web. That’s one thing that I think we’re particularly attuned to. I also think we’re a really good platform for poets and writer who maybe have never coded before. We’ve had a few who figured out what they want to do in this medium in a more active way, and I think we’re good for that. And likewise, we’ve had multiple people who’ve come from whatever technology background or art background who’ve never gone through a real, serious, rigorous literary editorial process. And we can offer that to them and be like, “Okay. You’re a real writer now. We’re gonna think about every single word and we’re gonna think about where that comma goes,” you know?

KG: How often—because that is an interesting balance to have—how do you strike that balance between showcasing debut writers versus having established people that you publish? And what are the differences in that workspace?

M N-C: I think it’s a balance we’re finding (laughs).

KG: Fair.

M N-C: It’s the honest truth. I mean, it’s a great question, and it’s one that we’ve been thinking about a lot. And how to navigate that has been a really interesting question. But I wish I had an answer, but I’m not sure I have a good one (laughs).

KG: That’s totally valid. What about you, Shelby?

SW: I also am not sure, but one thing that came to mind is that when we are putting the issue together, we think about the issue as a whole. So some of these pieces end up being in conversation with each other, and these themes and threads emerge as we’re going through the editorial process, which is always really interesting to see and I think is a result of that mix of different backgrounds and different experience levels with literature and coding.

KG: How do you two see e-literature changing in the future?

SW: I think it’s still kind of on the edges, maybe, and I think it will become more and more common and maybe the default of what we see, even, at some point.

M N-C: Yeah. I think one thing that I hope will happen more but I do think is going to happen more—it’s not just wish casting here—is that we take in a lot of text now through the web browser. And I think that the thing we’ll see more of is people playing with and reckoning with what that means as a medium. There will be more sort of interest, in all sorts of ways, in acknowledging that a piece may be living on the website of a newspaper is more clearly like, no, it’s clearly living on a website in a browser window. And what does that mean? And how does that change it? And I think that’s true of literary magazines, too. And I think there’s real symmetry here, too, with how much the physical object of print can change based on its dimensions and nature and how much that can change the experience of reading it. I just think there will be more awareness of that—of the medium itself.

KG: How do you think that the medium of seeing art online changes or enhances that experience as opposed to something like, you know, a newspaper?

SW: I think the portability is something that can enhance a piece. It’s on your phone if you want it. It’s on your computer. You can send it as a link to somebody. And the availability of it, too, goes with that.

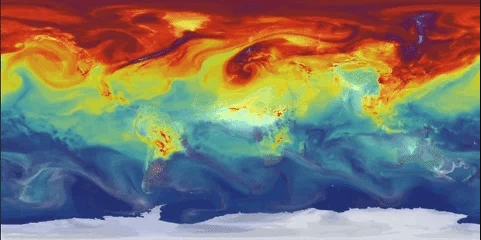

M N-C: Yeah. I think what Shelby said is so smart. It is such a different sharing and social experience of reading, and the way pieces can disseminate is very different. I also think a lot about—at least right now, it’s also, like, a very fragile medium (laughs).

KG: Interesting. Tell me more.

M N-C: Digital archiving is really hard and often dependent on extremely malevolent actors (laughs) whose only motivations are, you know, next quarter’s fiduciary responsibility to shareholders. The web, as we’ve seen many times, is really—contrary to what Shelby and I were told by authority figures as kids—it is not written in ink. And things can disappear incredibly quickly and become lost incredibly quickly. And there’s obviously ways to fight against that, but at the same time, there is something really interesting to me about the fragility of the medium, and that it requires trust, and all sorts of human upkeep, and relationships.

KG: Yeah, we’ve experienced that a lot, even in our journal, as well. That some of the old links—it’s like you’re walking through a ghost town in some cases, where some old links stop working and yeah. I imagine you guys have experienced some of the same things.

SW: Definitely. And in our first issue, Everest Pipkin made a piece called “Anonymous Animal” that deals with all of that and talks about a lot of that: links decaying and even, you know, elements on a page that don’t work anymore that once worked.

KG: How do you view the intersection between A.I. and e-lit?

SW: Yeah, it’s tricky. It seems to be everywhere now and I think a lot of artists have—including myself—anxiety about A.I. and, like, using it in a responsible way. You know, there’s all these implications with the environment and creative ownership, too. But I think it can be a tool that can enhance creative expression, too.

M N-C: Now that it’s a consumer product, I’m much less interested in it editorially. The reason I did have more interest before—and I still in theory have an interest in this—is that when people are authoring their own LLMs [Language Learning Models], that’s kind of interesting to me. When people sort of had their own hands in this thing that they’re creating. That, I actually think there is potential for an interesting intersection. But since it’s become using a product, immediately, my brain is just like, “Ugh. I’m so bored of this” (laughs). And I don’t know if that’s fair or doesn’t make sense but that’s kind of how I’ve experienced it.

KG: What is it about it being a consumer product that removed some of that magic for you? Is it the lack of dialogue between the creator and the creation? Is it the consumerism of it? What part of it?

M N-C: I think that—it’s not just with this, with everything—both Shelby and I love hand-written code, for lack of a better word. When you can go on someone’s website and see that they just—even with really bad, janky code—made it themselves, that sort of authorship. I’m always charmed by that. And I’m charmed by that in any situation. Like the indie game Balatro that’s been really successful over the past year. That developer showed his source code and this game, which has become really famous and sold millions of copies—and it’s a card game, based on a deck of cards—and it turns out that, like, a huge portion of his source code is fifty-two “if” statements for each card.

KG: (gasp of disbelief)

M N-C: You know, it’s written in this way that is not how a super aggro tech industry coder would do it, and I just love stuff like that (laughs). Where it’s like, yeah, a person made this. Like, computation is not this…black box of whatever. People made these things.

KG: If you could tell the world anything about e-lit, something that you really want everyone to know about the medium, what would it be?

SW: I hope people know that it’s accessible to both create and consume.

M N-C: That’s so good, Shelby. I hadn’t thought about the—yeah. I think what I would say is that they’re already consuming it. That’s what I would want the world to know. That, like, we are already consuming these things, and we may not be taking full advantage of that potential. We are already getting a lot of literature through electronic means, and we can take advantage and experiment with that.

KG: All right. Thanks so much for chatting with me today. Readers, if you want to see more of what these guys are doing, head over to this website address: thehtml.review. And if you want to see more from us, The New River, you’re already in the right place. Happy reading!