Fall 2021 Editors’ Note

By Adam Eddy and Amanda Hodes

Upon opening the Fall 21 issue, you might be surprised to discover its breadth. Although The New River’s issue contents have historically been in the single digits, this season’s comprises 14 individual pieces, including an interview feature with writer and artist Lillian-Yvonne Bertram. Each work is strikingly different from the next, as the genres range from speculative interactive fiction to online sound installations to generative cruft.

As new media and digital writing continues to evolve, we’ve found that the line between our “literary” and “visual art” submissions has blurred. In fact, the boundaries of what constitutes digital literature and art has become more complex and–from our perspective–exciting. We edited this issue with an open enthusiasm toward works that engage digitality, rather than approaching it from a gatekeeping perspective. Upon encountering the following pieces, we were astounded by their ability to reimagine platforms, de/encode language, subvert expectations and agilely channel them into new outlets–all this without losing a pulse of emotiveness that kept us engaged. Even at their most experimental, we felt that these pieces had a deeply human vein. They share a concern with culture, sociopolitical context, the environment, our planetary futures, and our interpersonal (mis)communications.

* * *

A Poetics of Commands

By “commands,” we refer to computational commands, of commands between coded action and reaction. One trend that we noted among a handful of pieces was their use of poetic language to interrogate coded language and systems. In “Handling Errors,” Kimberly Lyle makes this explicit through her constraints. Each sonic “conversation” is limited to the vocabulary of error functions in languages such as Python, Swift, Bash, and others. Meanings swerve between the two speakers, as intonation and cadence rush in to fill the semantic gaps.

In “Every tongue, that wound my heart,” Nilufar Karimi and Eliseo Ortiz explore the embodied, intergenerational, and varied natures of national anthems. They ask, “What does your body do when it listens to a national anthem? What do you see? […] How does your heart beat?” In the linked fullscreen diagrams, the contours of the anthems’ lyrics become the contours of a heart and eye. In this way, anthemic language seems to become somatic, carried deep within the arterial chambers, just as it is projected outward through perception (the eye, as well as the listening ear).

Caleb Foss’s “Binary,” too, considers the relationship between language, the body, and coded systems. Foss writes, “Binary is a generative text, which explores a non-binary body inhabiting a binary medium.” The piece unfolds linearly, as the location of the animation state is passed from one viewer to the next. At varying intervals, blood drains “from the spinal cord to the pinky toe” or conversely “saliva flows from the pinky toe to the eyeball.” The perceived “natural” pathways of the body and gravity are rerouted, a gesture that we read as an indication of the ways that binary code can be reductive of the complex, multifarious flows and circulations of bodies.

* * *

Reimagining Platforms

Many of the pieces in this issue reimagine the platforms, interfaces, or media that they inhabit. “CAPTCHA Poem@” by Tina Escaja adopts the ubiquitous internet CAPTCHA form and subverts it. The audio translation becomes a lyrical bilingual poem, and the CAPTCHA form becomes an acronym for “Completely Automated Public test to Tie Computers and Humans as Allies.” As part of a larger project, the piece also utilizes QR codes that have been posted around cities. Escaja writes, “Hence, QR codes blended with COVID paraphernalia that became oddly familiar, such as used gloves on the ground and requests for masks to enter buildings, etc. In a way, the city became an eerie ‘installation’ involving humans, codes and the virus.” In this way, Escaja not only reimagines the CAPTCHA and QR code forms, but also the city, as a site for technological and poetic intervention.

Likewise, in “Acts in Translation,” Dalena Tran crafts a sound installation for the internet browser. Within the computer “window” sits an architectural window; its interior lights flicker, sounds of the streets drift upward, and curtains billow out from the pane. Every hour, on the hour, a story is told about a broken heart. Like an installation, it seems to exist independent of the audience, continuing its retellings with or without any viewers. At once, we felt both voyeuristic as we peered in its partially obscured windows and also intimately invited by the voice and its emotive story.

Robert Spahr’s “Milton’s Balm Cruft” also unsettles our expectations of a static video piece. The piece regenerates daily during the early hours of 5am, drawing from images from 1980’s commercials, audio from Steve Jobs discussing Apple Computer and streaming internet radio 181.FM Oldies & Jazz Mix of the 1980’s. Taking material that is typically considered “throwaway,” Spahr crafts a unique work that interrogates our cultural American past. Yet, the work retains its ephemerality of capitalist commercialism, as each version disappears after its daily transformation.

* * *

Connective Circuits

Many pieces in this issue engage with ideas of connectivity or the new communication pathways opened up by digital media. Andrew W. Smith’s “Anti-Temporal Letters” for instance, imagines the digital communications of time-traveling rebels. This work, partially inspired by Janelle Monae’s music video for “Q.U.E.E.N.”, explores the potential of new platforms to collapse expanses of time and provide for anti-temporal linkages that can outlast our temporal bodies.

Also deeply invested in the connective potential of screens is “Motto” by Vincent Morisset, Sean Michaels, Caroline Robert and Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit. This work is built specifically for phone browsers and gives the viewer an opportunity to co-author the experience. Composed of thousands of tiny videos, ambient narrative, and opportunities for interactivity, “Motto” dissolves the typical barrier between artwork and viewer. The user’s phone camera becomes a tool for collaboration by allowing anyone to contribute to this vast archive of moments. Geographies, identities, and emotions are blended in a fascinating mesh of connections made possible by this emergent platform.

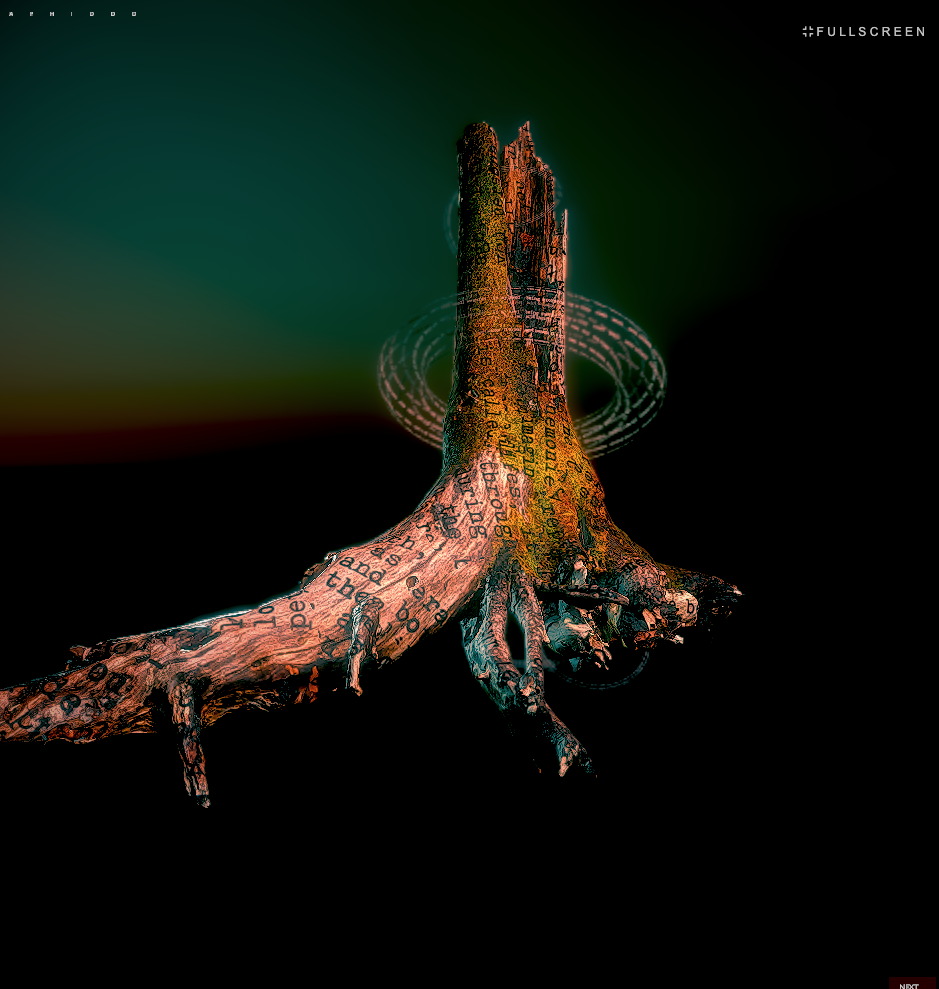

Nick Monfort’s “Arf Magna” takes communication into the spiritual realm by imagining connective circuits between life and the after-life. Dedicated to his dog Pepys, “Arf Magna” uses a single page of HTML text to create an interactive visual and sonic experience that references Ramón Llull’s Ars Magna. Published in 1305, Ars Magna allows readers to produce different propositions about God by combining sixteen dignities on a paper wheel. In Montfort’s work, the user’s cursor position on the screen changes the text, background color, and note being played to create a conversation of sorts between us and a cosmic best friend.

* * *

Documenting and Critiquing Contexts

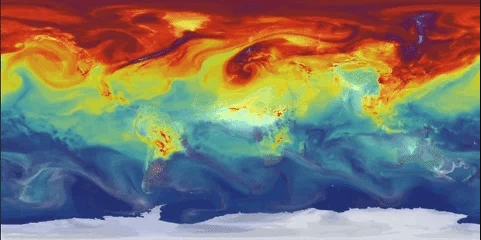

Many works in this issue also exhibit a kind of institutional critique made all the more vital in a digital context. Jonah King, in their work “HistoryOf.Golf,” analyzes the humanitarian and ecological devastation caused by westward expansion in America during colonization. By composing a detailed history of the game of golf, King focuses our attention on a performative manifestation of this land grab. They use the same ultra-widescreen format as the 1962 film How the West Was Won and footage of two middle-aged men golfing in the Mojave Desert to illustrate the continuing climate disaster and desertification resulting from capitalist expansion.

Documentation and context have been central in our world during the age of COVID-19 with more emphasis being placed on social responsibility and the restricted movement of individuals. Jody Zellen, in her piece “Ghost City – Avenue S,” explores the fractured and isolated experiences of those living in cities during this time. She created an interactive pandemic journal of sorts that uses images, text, and animations accessed through user participation. The resulting experience explores our struggle to create meaningful connections and identities during a time of isolation. By challenging the typical context of ‘public art,’ Zellen is able to welcome us into her lived experience from anywhere in the world. This subversion of the personal/public spheres creates new opportunities for community in digital space.

Owen Roberts, in his interactive piece “Garden,” creates a gamified interpretation of Hieronymous Bosch’s famous work The Garden of Earthly Delights. This triptych from the early 1500’s explores the devastation brought about by the earthly sins of man in a Christian context. Roberts, however, repurposes this narrative to examine the ecological devastation being brought about by human consumption. Navigating a crudely drawn landscape populated with burgers, dead animals, tech gadgets, and creatures of all kinds, the user is immersed in an apocalyptic world of waste and decay. Roberts uses the medium of video games to refresh an ancient parable for the digital age, reminding us that the dangers of excess have not lessened since Bosch’s time.

* * *

Finally, our last contribution to the issue will be by digital artist Herdimas Anggara. His platform sabotaging piece will be premiered and performed at our Zoom launch event on December 3rd. Not only does Anggara recalibrate the possibilities of the Zoom interface, but he has also prompted us to reinvigorate the static nature of our issue publication, as his piece will be recorded and added to these contents after the event. Overall, we remain deeply grateful for work that continues to surprise, challenge, and inspire us. As ever, we send particular thanks to our enduring supporters in the Virginia Tech MFA in Creative Writing program, including our founding editor Ed Falco, as well as to the broader electronic literature/new media community who have continued to trust The New River as a home for their work.