Editor’s Note: Fall 2019

By Tolu Adeyeye

I reflect on this edition I think about one of the major contemporary political issues of our time that reaches into the past and into the future.

Nature. The Earth. Climate. The human body. The human soul.

Many of these pieces evoke the cries of the earth under the scorching fury of our activity as humans. These pieces speak to the earth and the earth speaks back to them, creating a dialogue that begins in the soil and moves into the soul. Earth to Human. Human to Human. Human back to the Earth. I see these pieces, in collection, as a journey from the soil into the human mind. And if we are to regard media as a means of communication between humans, we can therefore understand how new media is an apt form of art for reflecting the current dissonance between the earth and the people who call it home: technology has both bridged the distance between humans, allowing us to communicate with people across the globe, as well as being the force that has damaged people’s lives; we as humans have a better understanding of the earth and its physical and biological systems than generations before us, while also almost unable to hear its cries—or, rather, we are not ready to truly listen.

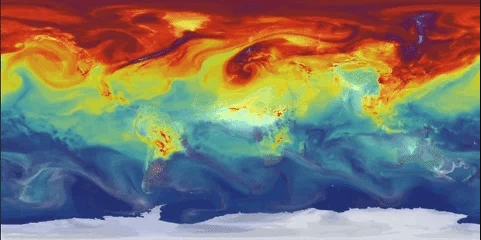

Waliya, Yohanna Joseph’s “Climatophosis” poses the larger question: who is to blame for the climate crisis? Joseph’s poem, in both English and French, is casted across a global temperature map. Both the map and the poem moves. The map gives a visual sense of that the world is changing, that nothing, not even temperature, is static. In this, a reminder that time is running out. The poem drops from the top of the map and then flows across the space, its movement rapid, English and French mixing together. Because I barely had the chance to read the poem to completion before the English and French collided, I felt as if I could not catch the words—in essence, I could not listen to what the earth was saying. When I hovered my mouse over the words, they froze, and I listened.

“Shadow Trees”, by Jody Zellen, takes us down into the city, forcing to stare at the way that even in the concrete world, nature is still present. It explores the way that even within the constructs that humans have built, we still need trees—to breathe, to live. And while most of us who are born and raised in cities don’t pay much attention to them, their shadows loom over us, and as we cross through them, their shadows darken our sight, if only for mere seconds. Zellen is able to capture the meeting point between trees and the urban world, which leaves me wondering, if, in the city, we had no trees, if all the trees disappeared one day, would we notice their absence?

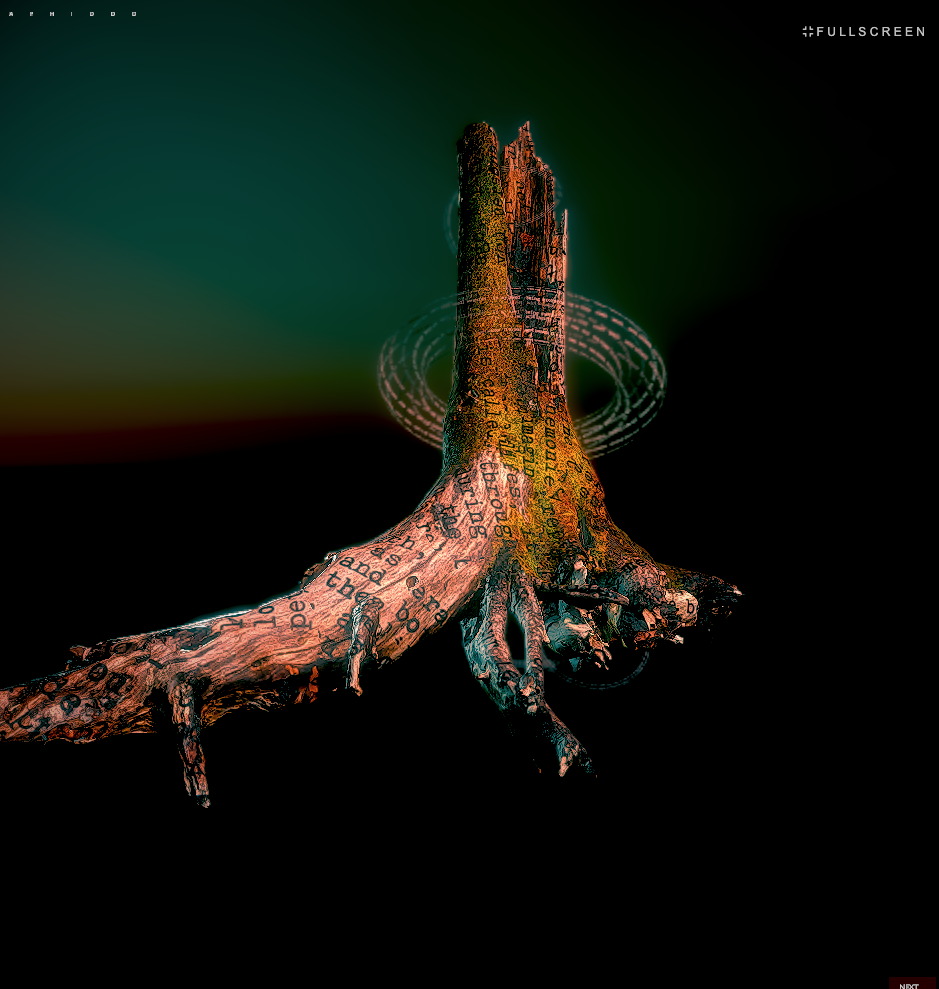

Andy Campbell’s “Aphiddd” brings us closer to the tree. In “Aphiddd”, Campbell amalgamates eeriness and etherealness to create a fascinating sensation of longing, lostness, and loneliness in the reader. The poems in “Aphiddd” move around the trees, wrapping around the trunks and branches, forcing the reader to twist and turn the trees in order to gain some sort of comprehension. I became attached to the trees as I read, my emotions gluing to their branches and their emptiness as I searched for answers. The series of trees and poems heighten the sense of bewilderment with which you begin; the play on language and letters shrouded by darkness evoke confusion and isolation. I enjoyed having to move the branches around just to make sense of the poems winding endlessly.

“We Descend, Volume III” by Bill Bly takes on the distance of memory and how memory fades. “We Descend” is rooted in the earth and the sky and the space between. It takes you on a journey through the minds of many texts which join together to form a narrative that can be rearranged and travelled through in numerous ways; “We Descend” offers more than one way to descend through the story: you can simply press next and go through consecutively; you can click on hypertexts which elevate the ideas of the hypertexted words; you can click on hypertexts which take you to a different text, thus debasing the idea of ‘narrative’ as a continuous stream. This, for me, evokes the weakness and uncertainty of memory and emotion—what can we remember about what we once felt? How accurately can we convey those ideas, to others and to ourselves? Bly grounds these questions in the way we see the world, both physical and non-physical.

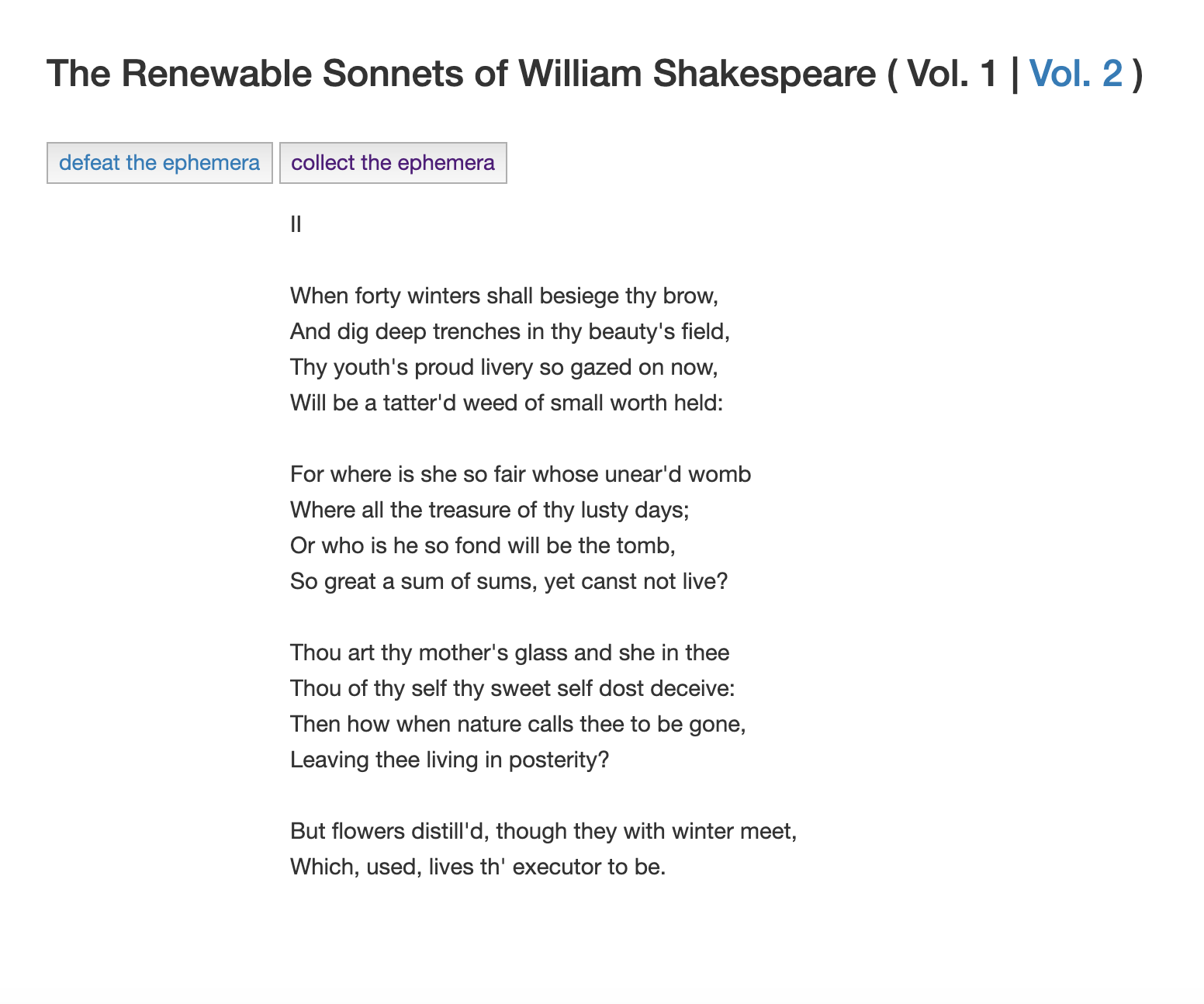

Curt Rode’s “The Renewable Sonnets of William Shakespeare, Volume I & II” buckles down on language itself through self-stirrable sonnets in Vol. I, and continuously stirring sonnets in Vol. II, for which you can ‘collect the ephemera’—screenshotting the poem instantly. Volume I allows you to distort language by running your mouse over the lines. Each line changes, or regenerates, as you do so. On first sight, this piece is simply fun, mainly due to the creation of jarring lines which do not match. When one probes deeper, one is required to ask, what is language? And since all these sonnets were created by one man—Shakespeare—can they be construed, mixed, combined? Volume II is like a reel—you are required to press ‘Thou shouldst print more, not let that copy die’ in order to generate a sonnet you can read clearly—stop, listen.

Lastly, Alan Bigelow’s piece, “The Forever Club, Episode 6: We Prepare To Die”, is the most technology-focused piece of the edition in terms of subject matter. It follows four main characters as they contemplate the end of the world, due to climate change. “We Prepare to Die” follows the characters through their phones: texts, social media posts, ads they see/watch, among other things. We know the characters only by what they do online. The episode encourages interaction with the reader through pop-up elements such as polls and interactive messages, and is comedic as well as sobering. This piece dives deep into the emotional by exploring friendship in the face of climate disaster; you are forced to wonder whether in the threat of an apocalypse, you too would be on social media searching for updates, or whether you would be focused on spending your last days, hours, minutes, with your loved ones.

What I most enjoy about this edition is the way that it reaches into the earth as a complex entity and into the human as a complex entity, and bridges the distance between, as a way of reminding us that we are dust, and we will return to dust, and when all is said and done, we are not mightier—not than the sword—but than the earth. If the earth perishes, so do we.