Spring 2021 Editors’ Note

By Amanda Hodes and Sonya Lara

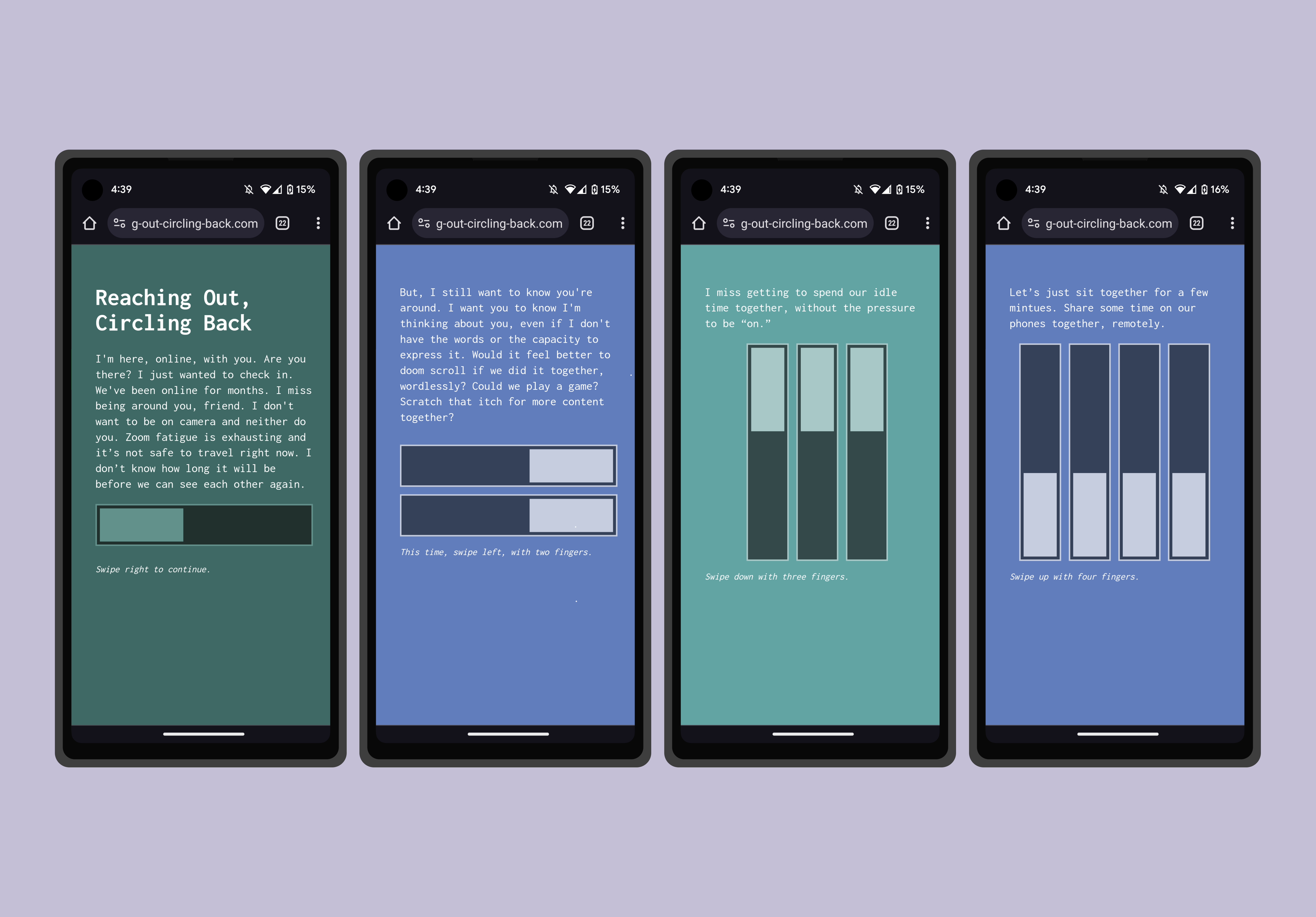

Our spring 2021 issue arrives over a year into the COVID-19 pandemic. Arguably, we’ve integrated ourselves into digital spaces more than ever before: workplaces have morphed into Slack, classrooms have become Zoom rooms, conferences have trickled into Discord, and social events have turned into FaceTime calls. Although we often frame this digitalization as a limitation, the work in The New River continues to remind us of the innovative affordances of digital creation and connection.

This spring, The New River received the most submissions in its history–more than a 200% increase compared to 2020, primarily due to the privilege of connecting with artists worldwide through additional digital outreach platforms. This substantial increase is a testament to artists’ desire to use digital media to comment on and critique the technologies and digital systems we exist within. The works in this issue echo the incredibly varied experiences of individuals over this past year and demonstrate the strength of unwavering voices finding renewed life through digital creation.

Undergirding these artworks is the tension between erasure and recovery, linearity and returns. In “Árboles de mi Desierto: Windsongs,” León de la Rosa Carrillo writes “the way through es volver atras.” For many artists, this return is a mode of standing against censorship. In Winnie Soon’s “Unerasable Characters III,” the undeniable push and pull against silence cannot be ignored. Reading becomes a newfound way to cling to the power hidden inside a voice. For others, the act of returning is a way of interrogating our relationship to time itself, especially nonlinearity and computerized time. Within these artists’ disparate approaches is a shared emotional investment and purposeful experimentation that asks readers “will you hear me?”

__________________________________________________

A Web Odyssey

Serge Bouchardon’s “A Web Odyssey” is an interactive narrative that reimagines Ulysses’s travails as a metaphor for the digital age. Through this playful yet incisive lens, Bouchardon probes the role of free will, surveillance, networks, and consumption in our webbed existence. Each ‘book’ offers a unique experience undergirded by immersive and nuanced world building.

In the “Lotos Eaters,” for instance, he invites readers to take a fate-driven journey while also promising the comfort of “feeling at home.” Readers are offered bliss through the promise of an enchanting spell. The Lotos flower derives its power from its ability to impart comfort through the temptation to live inside a memory. In order to continue the rest of the digital journey, readers must break out of the never-ending forum board. Almost immediately, readers are put to the test. The offering of the Lotos flower may seem impersonal but the forum board offers countless beautiful pictures and happy posts. How far will you scroll? How great is your desire to read all that’s offered? Will you return to your life outside of this digital creation or will you explore longer and put off returning to “the real world” a bit longer? The promise of a possible connection to other participants causes readers to question if they’ll ever leave. This eagerness to tap into one’s curiosity is a new style of erasure–– there’s loss in the decision to leave a world behind in order to press forward in the digital creation.

Unerasable Characters III

Winnie Soon’s brilliant piece positions technology as both a new and ever-changing framework for language. There’s a battle of erasure––a question of will and preservability. How does technology both disrupt the immobilizing act of silence and also perpetuate it? Here, technology instills a unique way of aging a voice through the use of emoticons and symbols. What do those symbols and emoticons mean in 2021 as opposed to 2025? Which will continue to be used and which will fade away to make room for new symbols? How do their uses vary among different users and how do those varied interpretations push and pull against one another? Protection and loss are intertwined through the use of the black backdrop. The darkness allows the remaining symbols to be easily read but it also serves as a reminder of what’s been erased and what could potentially be erased. This piece both freezes time and begs readers to question what will inevitably change or be lost.

They Were There When the Noise Started

“The loss of control often extends to human voice, human agency.” Gallerneaux’s “They Were There When the Noise Started” immediately poses the question: what does it mean to truly be alone? While Gallerneaux narrates, distorted pictures and video clips fizzle and quake across the screen, never fully revealing the images making up the background. Vision is skewed until each viewer’s desire for control is replaced with intrinsic curiosity. Much like the opening story, viewers must leave behind their preconceived notions of what it means to communicate and instead be willing to “talk [and listen] to the table tonight.”

Similar to “Árboles de mi Desierto: Windsongs,” Gallerneaux’s piece plays with cyclicality through repetitious images and videos. Focusing on minute details that continually play back, viewers are invited to peel away layers of meaning while gathering new information being recounted to them. Agency, voice, and time are both interwoven and pulled apart to question humanity’s ability to control the stories that are told. Gallerneaux dissolves the notion that a physical body is necessary to describe an experience. She explores the voice as medium between the ghosted body and language itself. Stories, and a being’s voice, never seem to fully disappear which begs the question of the power behind language. Viewer’s can’t help but also form a connection back to Soon’s revolving framework of semiotics and battle of erasure in “Unerasable Characters III” as they piece together what it means to exist in a world with palimpsestic, overflowing voices.

Árboles de mi Desierto: Windsongs

In “Árboles de mi Desierto: Windsongs,” León de la Rosa Carrillo explores the fissures of language and perception. By manipulating panoramic photographs of the tree that fell in the speaker’s yard, Carrillo creates shapes that are at once organic and angular. The first image closely resembles an organ, even a heart, as it pulses against the screen–and like a heart, this is the form we return to again and again while navigating the piece’s circuitous pathways.

As mentioned earlier, “the way through es volver atras.” Returns and cyclicality feel essential to this piece, both in subject matter (the tree dying and giving life to new sprouts) and the form (nonlinear pathways and the text strung around the photographic forms). In the visual arrangements that follow, images splinter into pixels as the perspective zooms in. Similarly, under such close inspection, the text also becomes evasive–breaking and skittering away. In this manner, the poem seems to ask to be read with its fractures, and its development refuses to be “dolled up como progreso.” Like the tree that refuses the “aberración of being upright,” the text rejects the linearity and teleology that stifles its multitudes. This sheds light on the panorama’s role in the work, as well. The panorama is inherently linear, a reel of successive photographs. By altering the unnatural panorama form into the organic, heart-like shape, Carrillo reclaims the aesthetic and lingual richness of the knurled and knotted. What initially catches the eye as ‘deformed’ is in truth ‘reformed’ and ‘informed’ by an astute awareness of linearity’s oppression.

Dante’s Academia

“Nothing else exists but us and this music.” Julia Sebastien expertly provides a direct connection between the players and the online game through immersive character conversations. While exploring the buzzing mosh pit at a party, several unnamed characters believe it to be different years––2010 and 2014. Here, Sebastien questions the complexity of time. What’s being said in holding onto those years? What years might players be holding onto, if any? Time cannot be bottled except through memory and the body. This virtual party allows these characters to connect to a specific time they cherish. They both reminisce together and individually, causing readers to think back to Bouchardon’s “A Web Odyssey” and the eating of the Lotus flower in Greek mythology. The mosh pit illustrates the body’s friction against productivity and efficiency in academia, acting as both a propellant and a temporal obstacle.

Sebastien’s piece also comments on the nuances of life through lines such as “I have no idea where this path leads, I’m so tired” and “I wish I knew where they all lead from the start.” There’s a desire for knowledge and a desperation to skip failure. Uncertainty is not always cherished or wanted, as seen through readers playing the game as well. What’s lost in gaining knowledge? What’s gained in slowly learning which paths lead to the next part of the game? Again, there’s an active push and pull in losing something in order to gain something else–in this case, the temporary body for the immortality of so-called “pure” knowledge.

Kinesics of Letters

Tiio Suorsa’s “Kinesics of Letters” takes a magnifying lens to the experience of pandemic isolation. Each video poem represents one month of lockdown life, exploring both containment and entrapment. In the bookended videos “March” and “June,” scattered text grazes and bumps against the edges of the frame, as though itching to break from their four walls. Each video, too, attempts to bottle the bizarre, new temporality of social isolation. As Suorsa writes, “Time has different shape[s] now, don’t you feel?” I add and bracket the plural ‘s’ here to highlight how each video distinctly renders those multivarious shapes. In “April,” the text curls into itself while being overlaid by refracted light. In “May,” much of the text appears to roll out of the frame, but the visual emphasis on glass and windows keeps the perspective enclosed despite the passing landscape. Does time reel away linearly? Does it wrap up into itself like a thread? Does it propagate, repeat, and scatter across the boxed spaces we occupy? I’m reminded of the definition of kinesics: “the study of the way in which certain body movements and gestures serve as a form of nonverbal communication.” In these videos, the text’s movement attempts to articulate the peculiar timelessness of lockdown–the contained, isolated motion within the world’s sudden halt.

At Nightfall, The Goldfish

Melody Mou invites disturbance through movement; a reader’s presence is always known through the rippling of digitized water. Prior to selecting each character to read about, text is blurred below the surface. In order to know the story, readers must click on each character’s name or title; they cannot just read the text below the surface––it takes action to know what happened. This action urges readers to fight against erasure as they scroll over each word to allow the poem to surface. “When I stopped walking, half my body was in the lake.” In order to hear each story, we must wade into the water. Readers are called to “find the lake and sink.” This both asks readers to read each section closely while also warning of the possibility of falling into the story too deeply. The line “he was watching the withered years” focuses the reader’s attention to the five characters placed in the shape of a clock. This symbolic design not only connects back to time but also death and the idea that each person within this piece either directly or indirectly has an effect on another’s life.

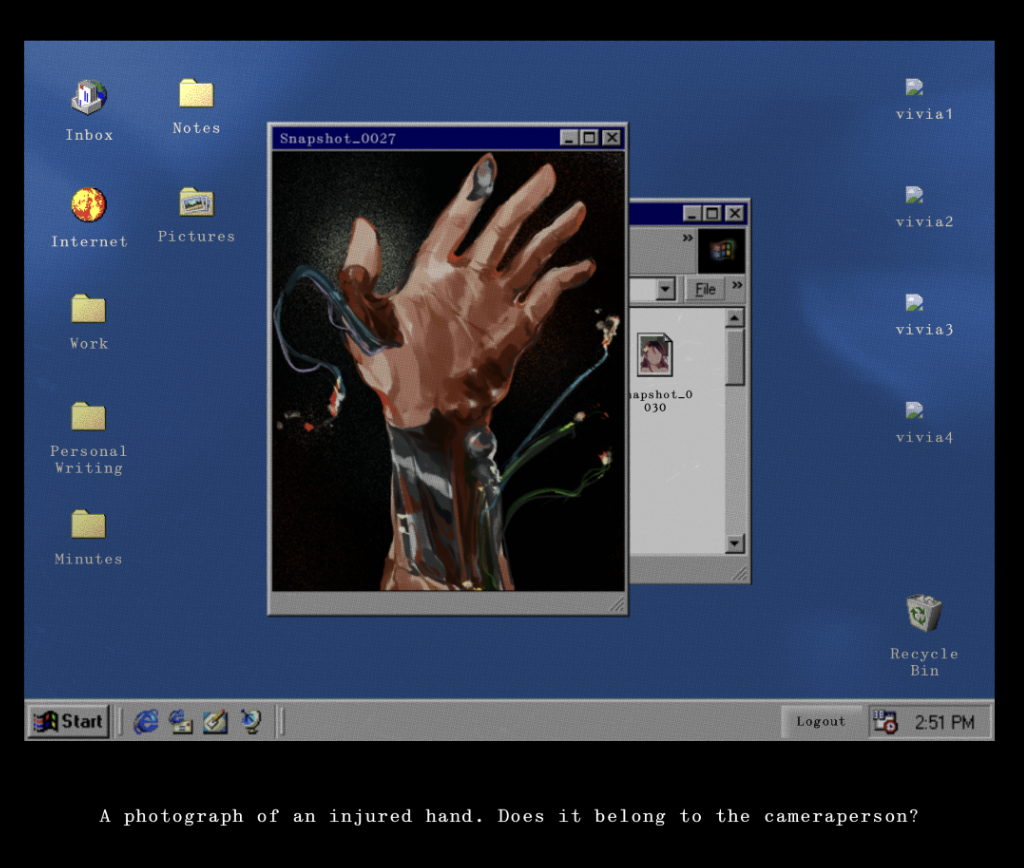

TOC: A Novel

We at The New River are honored to have the opportunity to publish this reimagined web version of TOC: A Novel. Originally published in 2009 as a DVD and then iPad app, TOC may be familiar to avid electronic literature readers, as it has won numerous awards (Mary Shelley Award for Outstanding Fiction and 2010 Gold Medal for Best Book Multimedia Produced from the e-Lit Awards, for instance). In its web form, this adaptation of TOC is preserved for time to come, or at least until some new mysterious technology takes the scene. While The New River typically restricts itself to unpublished art, and has certainly never published anything novelistic in scope, we make an exception in order to provide a platform for this important work. One can’t escape the self-conscious irony here of the phrase “to make history.”

Yet, on further inspection, this proves to be a revealing lens for analyzing TOC. Interrogating time itself, TOC crafts an alternate history and mythology of the world. It “makes” history in the sense that it is occupied by the material circumstances surrounding our bodily, ritualistic experiences of time. Time becomes something concretized and made–whether it’s through glutinizing sand in one’s bones or the visceral climbing and digging through futures past, pasts made future.

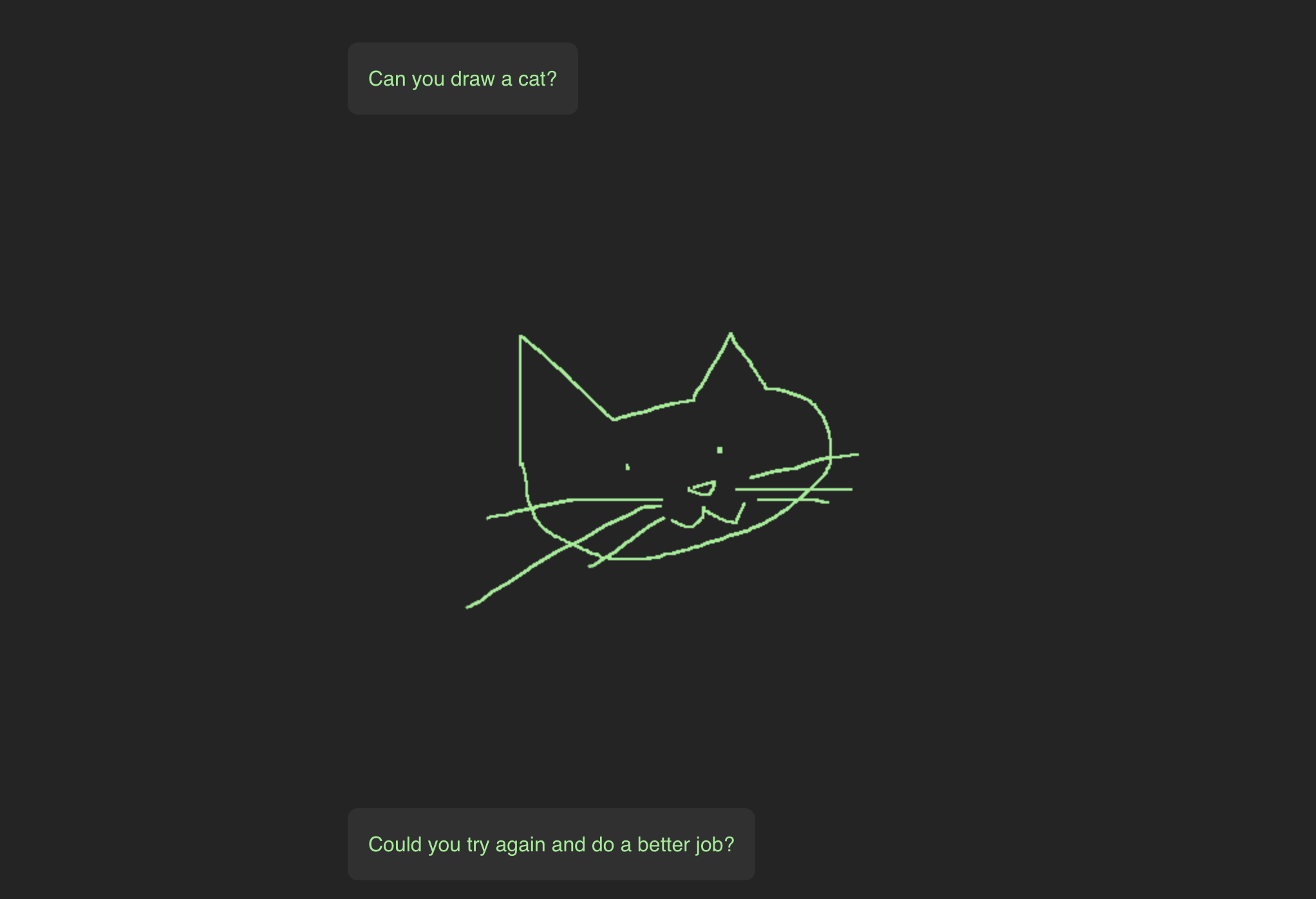

This makes a web version of TOC especially fascinating. Just as time is often thought to be ‘immaterial,’ so too is the web. To borrow scholar Nathan Jurgensen’s phrase, ‘digital dualism’ is the widespread belief that our digital and physical lives are inherently separate, and that one is ethereal while the other is materially ‘real.’ In recent years, this perceived binary has received overdue pushback as scholars and artists have reclaimed digital space as materially intertwined in our bodily experience (one thinks here of Legacy Russell’s manifesto Glitch Feminism). For TOC to enter the internet–distinct from the DVD or handheld iPad–feels to us an interesting shift in discourse surrounding the digital. It asks: what temporality does the webpage exist within, if any? How do we negotiate the gnarled yet liberatory relationship between the physical body and the digital? What do these distinctions between categories and types of time say about us–about our wants, needs, and experiences?

These are questions that we, as editors, have luxuriated in. We cannot thank our contributors enough for trusting us with their fearless, vibrant, and essential work. It’s a privilege to use this platform to share their voices, and we hope each reader forges a new artistic connection.